William Cardinall was born in about 1580 in Little Bromley, the eldest son of Charles Cardinall, and his first wife Elizabeth Suckling. The Cardinalls were farmers and clothiers, and the Sucklings were a well-heeled family from Norfolk. Elizabeth was, in fact, the step-daughter of Charles’ sister, Joan, and Joan was the 4 x great-grandmother of Horatio Nelson.

Charles and Elizabeth went on to have seven more children, the last being born in 1599, which is about the time Elizabeth died. Charles found himself a widow to marry; Bridget Bowes was about 39 when, in 1601, she and Charles were married at Little Bromley. Bridget brought with her four children from her first marriage to Thomas Bowes: her son Thomas, and daughters Anne, Judith, and Elizabeth.

In 1615, William Cardinall found out that his stepbrother Thomas Bowes had sold some houses in London and was willing to lend the money. William interceded: he knew a man in Norwich, one John Layer, who wanted to borrow some money, and so William acted as middle-man. Now, William’s sister Mary had married a Norwich man called William Layer, who had both a brother and an uncle called John Layer; it seems likely that either could be the man who borrowed Bowes’ money. Cardinall said that Layer put down a mortgage on some houses in Norwich, and borrowed £250 from Bowes. All was well. Cardinall went off to Ireland, but on his return to England he was horrified to discover that Layer hadn’t paid Bowes back. Cardinall was in an awkward situation – not only would it make family gatherings very awkward, but he appears to have been a signatory to a bond between Layer and Bowes. And Cardinall was skint.

So Cardinall thought that he would do his stepbrother a good turn. Bowes was living at Great Bromley Hall, and was a gentleman of means, having inherited property from his father, as well as from his maternal uncle, Ralph Starling. Predating Jane Austen by nearly two hundred years, Cardinall was of the opinion that, “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” Bowes had spoken to Cardinall on the subject; now living in London, Cardinall realised that he was in an exceptional position to match-make for his wealthy stepbrother. If he could negotiate a large marriage portion for Bowes, then he could expect a healthy commission for his troubles. This wasn’t Cardinall’s first foray into matchmaking; another gentleman had paid him for finding him a wife before, so Cardinall knew what he was doing.

Cardinall “did bend to his endeavours that way and att the last by meanes he found out as he thought a very fitting [potential wife] for him both in birth, worth and edicacon which was the daughter of one Mr Roe then living in London.”

Anne Rowe was indeed a good match for Thomas Bowes. Her paternal grandfather, Sir William Rowe, had been Lord Mayor of London in 1592, and was Master of the Ironmongers’ Company no less than five times. Her grandmother, Jane Lucar, was the daughter of Emanuel Lucar, a Somersetshire man who had used the Dissolution of the Monasteries as an opportunity to buy up huge swathes of his home county. Emanuel’s wife, Elizabeth Withypoll, was extremely well-educated and the brass upon her tomb at the church of St Laurence Poutney hymned to her extensive accomplishments.[1]“Every Christian heart seeketh to extoll The glory of the Lord, our onely Redeemer: Wherefore Dame Fame must needs inroll Paul Withypoll his childe, by love and Nature, Elizabeth, the wife of … Continue reading Anne’s mother was also a Rowe: Cicily was the daughter of another William Rowe, of Higham Hill in Essex, and his father, Sir Thomas Rowe, had been the Lord Mayor of London in 1568. Anne’s father was the great-grandson of Reginald Rowe of Lee in Kent; Cecily was Reginald’s great-great-granddaughter, which made Anne’s parents second cousins once removed.

William and Cecily Rowe had only had two children, Anne and Mary. It meant that Rowe’s impressive wealth would only be divided between the two daughters, and any prospective husband could expect a large marriage portion and, hopefully, some part of Rowe’s wealth on his death. Cardinall believed that Anne’s portion was a phenomenal £1,500, and that Rowe’s estate was known to be worth £500 a year. Bowes, wiping away his drool before it spilled onto his elaborate white lace collar, could hardly pass up such a bride. Cardinall said that he went into the country to tell Bowes about this fantastic filly, “which he tooke very thankfully.” A meeting was set up between Bowes and Rowe, “and good opinion each of the other wear taken in soe much as the said Mr Bowes conceived very good hopes of the match.”

There was a wedding. It is possible that the marriage in Barley, north-east Hertfordshire, between “Mr Thomas Bowes and Mrs Anna Row” on 9 December 1624 sealed the deal, and the couple had a 60-mile journey ahead of them to reach Great Bromley. Bowes paid his stepbrother £3 6s 8d for his troubles, but Cardinall thought this was rather stingy. So he went into Essex himself to pay him a visit.

Cardinall “found the said Mr Bowes somewhat strange towards him”, and Bowes took his stepbrother outside into the garden – where they might talk without being overheard by any of the household, including, one suspects, Anne. Bowes complained that Anne’s portion hadn’t been as good as he’d expected, and therefore he refused to pay Cardinall any further money. He was “willing to save his purse and not to deale soe freely” with his stepbrother; even so, he took £4 in gold from his purse and would offer no more. Cardinall accepted it, yet he was “in want.” His father had died in January or February 1624, a few months before Bowes hardwired himself into the grand Rowe family. Cardinall bemoaned the fact that, despite being the eldest son, he had inherited very little from his father – but it’s entirely possible that Charles had already bailed William out on numerous occasions, and was unwilling to bequeath him much.

All William Cardinall received from his father was “the £20 bonde which was dewe unto [William] as a dept frome Mr John Hassall and sete over unto [Charles] from the sayde William as a dette dewe unto [Charles].” Not much when his other brothers were receiving entire farms from their father – but his sister Joan inherited £20, his sister Mary Layer only received £5, and his other sisters, unnamed in the will, received £22 each. William instead presented this as “a great wrong” which had been “done unto him” by Bridget (his stepmother) and his brothers – they had “most injuriously” manipulated Charles “in the time of his great age and weakness” to disinherit William, and he griped and grumbled about Bridget’s “cunning practices”. As such, Cardinall felt that Bowes owed it to him: he’d had almost £8 now from Bowes for his matchmaking, “yet hoped Mr Bowes would some other waie be helpfull.” After all, Bowes was not only rich but well-connected. Couldn’t he put a good word in for the matchmaker?

On a trip to London, Bowes sent for Cardinall to the White Hart Inn in Holborn. This pub, on Drury Lane, is still open as “the oldest licensed premises in London.” Bowes offered Cardinall some money, but he refused to take it. And so Cardinall did what anyone else would sensibly do in his position – he took his stepbrother to the Court of Chancery.

Often Chancery documents only contain the Bill – that is, the complaint. It’s as if the Bill is enough to dissolve the deadlock, and the defendant, sighing for a quiet life, relinquishes their claim to a couple of pightles of land in a disputed manor, and things go on as before. But not Thomas Bowes. You may recognise his name – he has gone down in history as a persecutor of witches, the Justice of the Peace who, along with the brilliantly named Harbottle Grimstone, enabled Matthew Hopkins, The Witchfinder General. Kentwell Hall in Long Melford was used in the (historically inaccurate in many and varied ways) 1968 film Witchfinder General about Hopkins’ reign of terror. It was owned by the Cloptons at one point, and Thomas’ great-uncle, Martin Bowes, had married Frances Clopton. The Cloptons appear to have been linked to Thomas’ second wife, and all this led to Chancery suits from 1666-70 between Martha Clopton and Sir Thomas Bowes, fighting over Kentwell Hall and other property around Long Melford. What a huge irony. To return to the moany matchmaker, though, Bowes was not afraid of legal shenanigans. If his impecunious stepbrother was going to lodge a Bill in Chancery, then he wasn’t about to leave it unanswered. And so, point-for-point, Bowes replied to Cardinall.

The houses Bowes had sold in London were “old and ruinous”. And whilst he had lent John Layer the money, the man was a complete stranger to him – thus Bowes could roundly blame Cardinall for all the problems that followed, as he was the go-between and had failed to find Bowes a secure deal. It turned out that the houses that the money was lent against were charged with an annuity to support one Anne Layer, a widow, and it was almost up to their full value – the implication being, perhaps, that John Layer couldn’t pay back the money he owed as it was swallowed up in Anne’s annuity. Bowes quoted a mortgage dated 8 May 1618, in which Layer and Cardinall had assured Bowes that the houses were worth a lot of money and had a good income. They had misled him. Neither did matters improve on Anne’s death: the houses were occupied by “poore French and Duch people” – Huguenots, presumably – who paid a low rent, and the houses were in very great want of repair. An economic slump had affected Norwich, “which is of late very much decayed in all manner of tradinge.”

Bowes was painting himself as the victim. And Cardinall was being underhand, “the plaintiff [is] goinge about by multiplicity of suite to trouble this defendant.” Cardinall “hath stuffed out his bill” by referring to the matchmaking – for Bowes, the main problem was the mortgage – and he presented a very different picture of what had happened.

Bowes had a friend called Mr Price, and he claimed that was only via Price that Bowes came to become acquainted with William Rowe. Price was “the active man in the business” and Bowes, who clearly could not resist a pun when one raises it head, said that Mr Price “was a man of no price.” He would not be hassling Bowes for money, unlike Cardinall.

Bowes said that he had received “very reasonable conditions” from Rowe “and being well pleased with the virtue, bewtie and worth of the gentlewoman his daughter”, the marriage took place. But it was true that the portion was not up to snuff. And then Anne predeceased her father. The clearly bereaved husband opined, “all other possibility and expectation died with her,” as Bowes now would not inherit anything on Rowe’s death, so Cardinall’s demands were “altogether out of time.”

He absolutely denied that Cardinall had been hard done by. As Charles Cardinall’s eldest son, Bridget had request Bowes give to Cardinall “his very seale of armes”. Unfortunately the parchment which this part of Bowes’ deposition is written on is very thin and has buckled, so it is a challenge to read – it seems as if, when Bridget went to her son with the arms to pass to Cardinall, she had “many speeches” about her stepson, which were none too complimentary. Bowes concluded that Cardinall was being exceptionally unfair about Bridget, “out of a great deal of bitterness without any truth.” He knew that Cardinall had become very poor, but Cardinall was “insolent” – and Bowes was neither going to help his stepbrother, nor put up with being dragged through Chancery on baseless accusations.

Quite what the outcome was, we will never know as it is not included in the Chancery records. And unfortunately the Bill and Answer are undated – The National Archives’ catalogue can only give us 1625-60 as a rough guide. But by the time of the suit, Bowes had married again, to Mary, daughter Paul Dewes or D’Ewes of Stowlangtoft in Suffolk. Another wealthy young lady, Bowes satisfied himself with a large marriage portion “without the plaintiff’s help at all”, he added, in case Cardinall tried to make a claim against that as well. They were married in about 1626, and their first child was born in 1628. When Paul D’Ewes died, he did not leave Mary anything in his will, as she had already been provided for on her marriage, but the grandchildren were all left £100 each, and Thomas, the eldest of the Bowes’ children, was left £140-worth of plate, embossed with D’Ewes’ arms. In 1630, Bowes was knighted by Charles I at Nonsuch Palace. What great endeavour had led to his dubbing, besides being very rich and well-connected, isn’t clear.

And what became of William Cardinall? The 1634 Visitation of Essex shows that he one son, called Charles, perhaps in an attempt to win the favour of his father, and it says “now in Ireland 1634.”[2]Which might set the date of the Chancery suit between 1626-30 – Bowes is referred to as Mr Bowes, nor Sir Thomas Failing to make anything of himself in England, he had gone back to Ireland, but whether he continued his matchmaking endeavours is unknown.

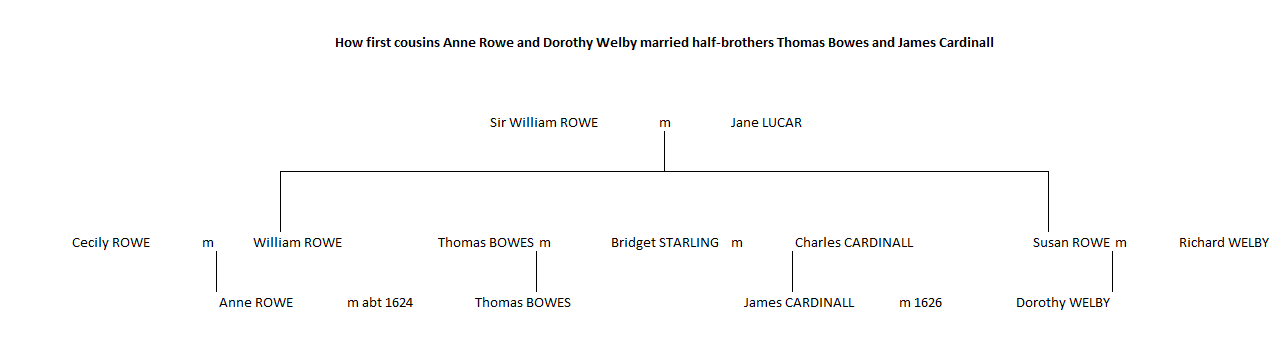

Then again – he might have. On 11 July 1626, James Cardinall (1603-1664), son of Charles and Bridget Cardinall, and therefore half-brother to both William Cardinall and Thomas Bowes, was married at St Michael Bassishaw in London. His bride was Dorothy Welby, the daughter of Richard Welby, a leather-seller in the City of London, who had also been a city captain and a deputy of Bassishaw ward. Welby’s wife was Susan Rowe, daughter of the aforementioned Sir William Rowe, who had been Lord Mayor of London – Susan was the brother of William Rowe, Anne Rowe’s father. In other words, James Cardinall had married the first cousin of his half-brother’s first wife; or Anne and Dorothy were first cousins, and they had married half-brothers. I appreciate that this is rather confusing, so behold…. a family tree.

Had William Cardinall a hand in this? Even though Bowes denied that he had helped him find his first wife, James’ marriage might argue against that. Then again, we don’t know how close James and William were – William was twenty-three years older than James, and although we don’t know Bowes’ date of birth for certain, as he was apparently born in East Bergholt and the early parish register hasn’t survived, he seems to have been about 10 years older than James. So it’s possible that James was closer to Bowes, and therefore the marriage could have come about through Bowes’ acquaintance with the Rowe family, and therefore to the Welbys.

It’s probably worth pointing out that even the mysterious Mr Price, the “man of no price”, might have had something to do with the Welbys. Richard was the son of Adlard Welby and Cassandra Apreece. ‘Apreece’ is a Welsh surname, from Ap Rhys, son of Rhys (it’s said that Cassandra’s family can be traced back to Mediaeval princes of south Wales), and, just as Ap Richard can be Anglicised into Prichard, Apreece can be mangled into ‘Price’. The matchmaker who Thomas Bowes claimed really helped him to his first marriage could have been a maternal cousin of Richard Welby.

The story of the Norwich mortgage and the war of the matchmaker has come from Chancery documents C 2 /ChasI/C30/54 at TNA, Cardinall v Bowes. I had thought it would be a dispute between James and Thomas, half-brothers warring over their uncle’s will, or over property as their mother died intestate. It turned out to be quite different! There is another Chancery suit, Cardynall v Bowes, C 2/ChasI/C17/56, dated between 1625-60 – this might be yet more argy-bargy between William Cardinall and his stepbrother, or it might indeed be Bridget’s sons coming to blows. Every trip to The National Archives, and every cardboard box of parchment, contains fascinating stories – and such unexpected detail. Bowes, looking at his stepbrother strangely, and then taking him out into the garden so that he might not be overheard by the household, makes both Bowes and Cardinall spring to life. And while Bowes is remembered by history as a persecutor of witches, we see him in these documents involved in awkward family wranglings, with no mention of imps and familiars, no Pyewacketts or Vinegar Toms, or Satan talking in a flat, deep voice. The devil, Bowes might have said, is a stepbrother who drags you through Chancery.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | “Every Christian heart seeketh to extoll The glory of the Lord, our onely Redeemer: Wherefore Dame Fame must needs inroll Paul Withypoll his childe, by love and Nature, Elizabeth, the wife of Emmanuel Lucar, In whom was declared the goodnesse of the Lord, With many high vertues, which truely I will record. She wrought all Needle workes that women exercise, With Pen, Frame, or Stoole, all Pictures artificiall, Curious Knots or Trailes, what fancy would devise, Beasts, Brids, or Flowers, even as things naturall: Three manner hands could she write, them faire all. To speake of Algorisme, or accounts, in every fashion, Of women, few like (I thinke) in all this Nation. Dame Cunning her gave a gift right excellent, The goodly practice of her Science Musicall, In divers tongues to sing, and play with Instrument, Both Viall and Lute, and also Virginall; Not onely upon one, but excellent in all. For all other vertues belonging to Nature, God her appointed a very perfect creature. Latine and Spanish, and also Italian, She spake, writ, and read, with perfect utterance; And for the English, she the Garland wan, In Dame Prudence Schoole, by Graces purveyance, Which cloathed her with Vertues, from naked Ignorance: Reading the Scriptures, to judge light from darke, Directing her faith to Christ, the onely Marke.” “The said Elizabeth deceased the 29 day of October An. Dom. 1537. Of yeares not fully 27: This Stone, and all hereon contained, made at the cost of the said Emanuel Merchant-Taylor.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Which might set the date of the Chancery suit between 1626-30 – Bowes is referred to as Mr Bowes, nor Sir Thomas |