Growing up in Wivenhoe, I probably saw a greater mix of people from around the world than had I lived in a town of the same size that wasn’t anywhere near a university. When I was five years old, there were some boys in my class at Broomgrove Infants who were from Peru! Their fathers were visiting academics at the University of Essex, you see. And international students from Africa and Asia and everywhere else in between made Wivenhoe their home.

But in transcribing the parish register for Wivenhoe, it seems that the town had been the home of people from afar before. With uncanny coincidence, while transcribing the 1751-1812 baptisms and burials register during October – Black History Month – I found references to Wivenhoe residents of the past who were black.

Now obviously these days, vicars don’t put a note in the margin to indicate someone’s ethnicity whenever someone is baptised or buried – this demonstrates that it was sufficiently unusual in the 18th century for their race to warrant a mention. But I think it’s very interesting that these notes appear, because it shows to us that emigration isn’t a new thing that only started to happen in the mid-20th century. The idea that Britain is a solely “white” country appears not to be true when you look at the historical record – and if you think about it, it would be very odd if it was just white – it’s a country that was in the middle of an empire that spread across the world.

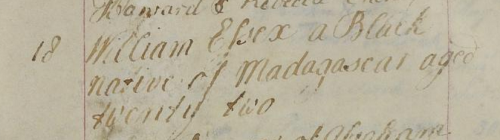

First, we have the baptism of William Essex on 18th February 1767 – presumably a name he was given or chose himself – “a Black native of Madagascar aged twenty two.” He doesn’t reappear, although there’s a Thomas Essex who got married in Wivenhoe in 1760 – is there a connection? In the 18th century, a black servant was a status symbol (rather than a boring, run-of-the-mill white servant), so William could have been employed by the Essex family, and taken their name. But considering the maritime business of Wivenhoe, it’s possible that William was a sailor – he might even have been employed by Thomas Essex in that capacity (I don’t know anything more about Thomas to make a guess, but there appears to have been an Essex family in Colchester earlier in the 18th century). Or it could just be that William’s surname merely reflected the name of the county he was living in.

It may be coincidence, or it may not, that over in St. Osyth on 2nd August 1767, John Africanus (methinks perhaps not the name given by his parents…) was baptised. A note in the register says “A black boy.” Living in St. Osyth, John could have been a sailor, or he could have been a servant at St. Osyth Priory – it was owned at the time by the Nassau family, and as you can probably guess, they were related to the man after whom the Caribbean island of Nassau was named in 1695.[1]William III, in case you were wondering, who was of the Dutch House of Orange-Nassau.

On 16th February 1802, Henry Phillips, aged 67, was buried in Wivenhoe. A note in the register says “A Black”, but unlike William’s baptism, we don’t have a note about where Henry had travelled from (if he had travelled from abroad at all – he may have been born in Britain anyway!). Henry would have been born in about 1735, so he may well be the same Henry Phillips who married in Wivenhoe in 1770, to Mary Smith. He signed the register, which says something to us about his literacy. They had three children – Sarah Mary (1771), Henry (1773-1776 – he died in a small pox epidemic) and Mary (1775).

I’d love to know more about William Essex and Henry Phillips – they were near-contemporaries in age and I wonder if they were friends? Perhaps they had both come to Wivenhoe together? It would also be interesting to know about the lives of the mixed-race Phillips children. I will keep my eyes peeled….

Images reproduced by courtesy of the Essex Record Office.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | William III, in case you were wondering, who was of the Dutch House of Orange-Nassau. |

|---|