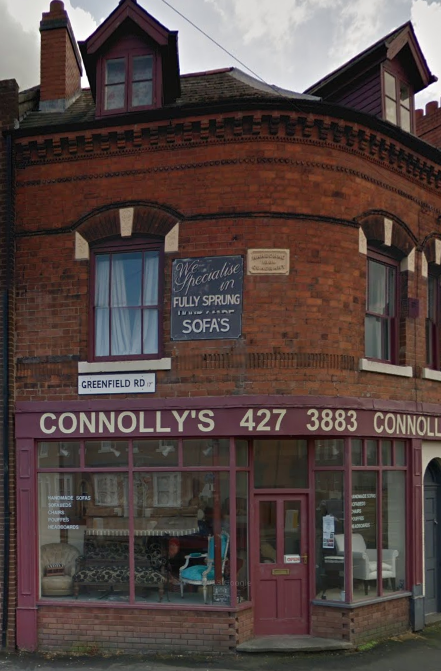

On the junction of Greenfield Road and Vivian Road in Harborne, Birmingham, some refurb work has recently taken place on what was once a furniture upholsterer’s called Connolly’s. I loved looking in the window of that shop – whether it was an old chair reupholstered in surprising new fabric, or a classic art deco sofa and armchair set, there was always something in the window that grasped my attention. But this morning, what caught my eye was this brick: is it really 132 years old?

Connolly’s has now closed, and the cornershop it occupies has been refurbed. I’m not sure if it’s a private home now, rather than a business, as the large shop windows now have a frost-effect covering. Beneath Connolly’s shop sign, an older one was discovered – from the time when the premises was occupied by R. O. Price:

The old shop sign is still there, and, as you can see from the photos, it’s one of those beautiful old signs which, in the West Midlands, you can only see now in the Black Country Living Museum! Ironically, this “high class grocery” is about 500 metres from a branch of Waitrose. I have tried to research R. O. Price – I think a trip to The Library of Birmingham to look at their collection of old Birmingham trade directories would solve it. This morning, however, I noticed the old brick, which is part of the step which leads up to the shop door.

I should at this point declare that when I was a child, my father was a builder and funeral director. It seems like an odd combination of jobs, but wasn’t unusual in small towns, where the two professions overlap – a builder has access to garaging for vehicles (where you can keep your trucks and your hearses), carpenters (who in the old days could build coffins as well as fitted wardrobes) and men who could equally dig foundations as well as graves. And with all those burly builders about, there were plenty of candidates to act as pall-bearers. So from a young age, aside from the funeral aspect of things, my father would always comment on brickwork and bricks – whether it was Flemish bond or Sussex bond, or if the bricks had a salt-leeching problem. So when I spotted this brick, I was intrigued, in a way in which, had my dad just been a bus driver, I probably wouldn’t have been (of course, if he’d been a bus driver, this blog you’re reading now would probably be about an interesting National Express coach…).

I was amazed that the stamp on it had lasted that long, but then I wondered if someone was making reproduction old bricks. If Price’s/Connolly’s had been renovated to the point that they’ve left the old shop sign uncovered, then might they not be the sort of people to preserve the character further by using bricks that were in keeping? There are plenty of companies which sell historic-looking bricks and fire-surrounds and all that jazz, so perhaps this is what I was looking at?

I asked about this morning, and the people behind The Register of One-Place Studies thought it should look a lot more worn for a brick that’s 132 years old. I’m inclined to agree. However…. if it was a new, repro brick, I’d be surprised if it was as rough around the edges as these clearly are. They looked quite bashed about. The other thing to notice is that the mortar has run into the name imprinted on the brick, which perhaps make the print look a lot clearer than it would’ve been otherwise. Has that mortar got into the lettering recently, during the refurb (I do recall them digging up the step and relaying it) or did it happen at an earlier point in the brick’s life?

It could be reclaimed brick – there’s a market for this, so that when Victorian buildings are pulled down, the demolition happens carefully to preserve the old building materials for reuse. So whilst we might expect a brick that had sat for 132 years outside a grocer’s and an upholsterer’s (and whatever other businesses went on here over that time) to be more worn, it could’ve been reclaimed from a location where it got far less traffic. In fact – Google Street View is still showing the pre-renovation Connolly’s, and if you look closely (don’t get distracted by the lovely furniture in the window) you can see that the step isn’t blue brick. So the Hamblet brick hasn’t been on that site since 1883 – it’s presumably come from a reclamation yard somewhere. Of course, this now makes me curious as to where those bricks have been for all that time. Did lots of people walk on it or not?

Hamblet’s closed in 1915, but someone else was trading under that name as “Hamblet’s Blue Brick Co.” in the West Midlands in the 1960s. So it could be that the brick dates from then, and they were stamping them with the “antique” year of 1883. That said, there’s several articles on the Black Country Bugle website about Hamblet’s, one of which says that the blue bricks were renowned in Britain for being extremely tough – the Institute of Civil Engineers ran a test on them in 1886 and found they won out over other makes, and plenty of examples of the bricks are to be found… well… everywhere you look!

So perhaps the brick I stood on this morning really was 132 years old after all.