- Home

- /

- History

- /

- Life at Weeley Camp...

- /

- Mary Ann Grant: a...

Pam Perkins, reviewing The Travels of Elizabeth Isabella Spence, says of Mary Ann Grant – author of Sketches of Life and Manners – that “there is almost no biographical information available on her, and she appears not to have published again after this book”.[1]Perkins, P. “The Travels of Elizabeth Isabella Spence”, The Bottle Imp, 11, May 2012 Glen Hooper says “Mary Ann Grant appears to be one of the earliest woman travellers to Ireland whose account survives, although it has not been possible to trace any biographical information on the narrator herself”[2]Hopper, G., ed., The Tourist’s Gaze: Travellers to Ireland, 1800-2000, Cork: Cork University Press, 2001. p. 13 When I first wrote about Mary Ann Grant, I was able to find out a few things about her, but nothing conclusive – I knew nothing about where she was born, and had no idea of what happened to her after she got up from her desk on finishing her book. But now I’m able to sit down at my desk and tell you the story of Mary Ann Grant.

The Yorkshire roots of a London girl

Mary Ann’s parents, Robert Nicholson and Ann Elizabeth Hepworth were married at St Martin’s-in-the-Fields in Westminster on 15th July 1770. Her father had at least one sibling – a sister called Elizabeth, but I’m yet to find out where the Nicholsons hail from.

Mary Ann’s mother, however, can be traced back to Yorkshire. She was baptised as Anne Hepworth, on 2nd August 1741in the village of Emley, which is now in West Yorkshire, between Huddersfield and Wakefield. She was the youngest child of Robert Hepworth and Mary Child, both Emley locals themselves, who had married in the village on 12th December 1725. It’s entirely possible that Mary Ann’s name came about as a mixture of her mother’s and grandmother’s names.

Robert and Mary had seven children between 1726 and 1741: Mary, Francis, Martha, Robert, Hannah, William, and Ann. Their eldest son, Francis, married Sarah Dison (another Emley local) in 1749. Their eldest child, Joseph Hepworth, went to Queen’s College, Cambridge in 1765, and became a vicar of several places in Norfolk: Felmingham, Suffield and Gunton with Hanworth, as well as becoming the headmaster of Wynmondham School and North Walsham School.

His younger brother William, born about 1758 in Emley, was also a clergyman who studied at Cambridge (St John’s rather than Queen’s) spending most of his life as a curate afterwards: at Happisburgh in Norfolk (presumably where he met his wife, Elizabeth Postle, who lived in nearby Oby), and from 1791 until his death, at Wattisfield in the north of Suffolk. For the last two years of his life, he was the rector of Congham St Mary in Norfolk, but he appears to have been rector in absentia, as he remained in Botesdale. William is the “Mr H” who Mary Ann wrote about in her letters, who she visited in Botesdale with her mother in 1800. He was Mary Ann’s first cousin, although there are over twenty years between them. He appears in the subscriber’s list of Sketches, putting himself down for two copies, which isn’t surprising as he’s in the book! He wrote his will in 1838, and he left his “cousin Mary Ann Grant, widow… £7 for a ring.”[3]Prerogative Court of Canterbury will of the Reverend William Hepworth of Botesdale, Suffolk: PROB 11/1947/125

London life

Mary Anne’s parents appear to have only had two children: John, born on 28th September 1779, and baptised on 22nd October that same year; and Mary Ann, born on 29th March 1781, and baptised 27th May. Both children were baptised at the Percy Chapel at St Pancras, which was very new as it had only been built in 1765. It was on the west side of Charlotte Street, immediately opposite Windmill Street.[4]LMA archive. Sadly, the two siblings never met, as John died as an infant, and was buried in Holborn on 13th September 1780.

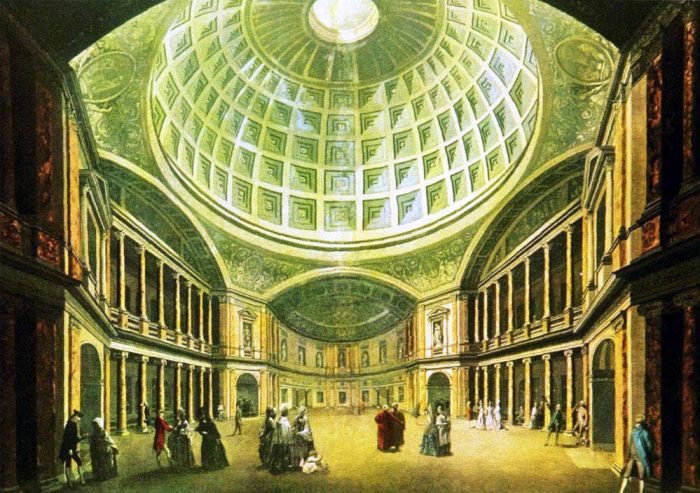

When Mary Ann was a child, her father was a victualler at the Pantheon Punch House on Poland Street, near Oxford Street.[5]His Prerogative Court of Canterbury will says he was a victualler of Poland Street, near Oxford Street, and Ed Pope’s notes on Poland Street show Robert Nicholson on that street at the Pantheon … Continue reading She grew up right in the middle of one of the busiest, most bustling cities on Earth, so it is no surprise that the Highlands of Scotland, where she would at one point live with her husband, was so different for her.

Robert’s punch house was right next to one of the entrances to the Pantheon, which was on Oxford Street, but also had an entrance on Poland Street. When it opened in 1772, it had one of the largest rooms in England at the time with a huge dome, and the venue itself as a set of winter assembly rooms. It’s not surprising at all that the punch house would capitalise on its proximity to such a venue and be called the Pantheon Punch House. The original Pantheon burned down in 1792, and was rebuilt, only to be demolished in 1937 (before Hitler could have a go), and there is now a Marks & Spencer’s on the site.[6]When I bought some trousers and a sunhat at that particular M&S, I had no idea it had once been the site of such an amazing building!

Robert died in 1789, when Mary Ann was only eight years old.[7]When he died that year is unclear, as I haven’t found his burial. He wrote his will on 22nd January 1789, and it was probated on 4th September the same year. There is a possible burial at … Continue reading In his will, he mentions that he owns the leasehold of two properties – no. 21 Tottenham Street, and no. 29 Upper Marylebone Street. His widow (named Elizabeth Ann in his will) and daughter were inherit the rents of these properties, so they were not left destitute. Robert stated that if Mary Ann died without issue, the inheritance would pass to his sister Elizabeth, wife of Samuel Turner. She might have been the Elizabeth Nicholson who married Samuel Turner of Ridgewell, Essex, at St George Hanover Square in 1777, but I haven’t been able to trace the couple any further.

Robert’s executors were to be his widow, and Walter Mills, a gentleman of St James Clerkenwell. But Walter died in 1791[8]He was buried at St Andrew’s, Holborn, on 7th February – in her letters, after her mother’s death, Mary Ann mentions that her guardians have died, which would presumably be a reference to Walter, as well as to her late mother, as Walter was supposed to take charge of the rents on the two leasehold properties.

Widowed at 48, and with an income, Mary Ann’s mother could have remained a “merry widow” in London. But life had other plans.

The several loves of Elizabeth Ann

Less than a year after Robert’s death, Elizabeth Ann married on 6th January 1790 – Epiphany or “Old Christmas” as it was known at the time.[9]Presumably it was called “Old Christmas” because it’s where Christmas would’ve fallen if not for calendar reforms in the eighteenth century. The groom was a widower, William Jenkins of Hammersmith, another victualler – it’s incredibly likely that Elizabeth Ann knew him through her late husband’s business. Of course, Elizabeth Ann probably had a hand in the running of the business, so the match would’ve been ideal for both William and Elizabeth Ann.

But tragically, the marriage would not be a long one. William died less than six months later, in June 1791. He left Elizabeth Ann a lifetime annuity of £10 a year.

Undeterred from matrimony, two years later Elizabeth Ann was a bride once more. She appears to have returned to St Pancras from Hammersmith, as she was “of St Pancras” when she married widower John Daniel Goll of Fulham at St Pancras on 8th March 1793. He is “Colonel G” in Mary Ann’s letters.

Colonel G

John Daniel Goll was born in Lanarkshire, Scotland in about 1733. He spent his life soldiering, joining the Royal Artillery in the 1750s. He became a 2nd lieutenant in 1762, a 1st lieutenant in 1767, a Captain Lieutenant in 1774, and a captain in 1780. In 1783, he became a Major, then he retired on full pay in January 1792, until in 1795 he joined the Battalion of Invalid Artillery and became a Lieutenant Colonel.[10]Sources: the Army List and “Royal Artillery Officers, 1716-1899” on FindMyPast.

In about 1760, he married Margaret Grossett. She was the granddaughter of Archibald Grossett and Euphemia Muirhead. Archibald was a merchant (Margaret’s uncle was born in Rotterdam), and Euphemia came from rather grand stock – her grandfather was Alexander Stewart, 4th Lord Blantyre. Margaret’s father, Alexander, was a soldier too, and was killed at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, when Margaret was still only a child.[11]Information on Margaret’s family drawn from Mother Bedford.

John and Margaret had several children, among them Miriam, John Alexander, Louisa Charlotte, Maria Theresa Victory, and Rosamond. The eldest were born in Scotland, while the youngest were born in London. Margaret died in Fulham in October 1792 and John married Mary Ann’s mother the following year.

In 1786, Miriam married Abraham Du Vernet at the church of St Clement Danes on the Strand in London. He was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Royal Artillery, so no doubt Miriam met him through her father. Abraham was posted in various places of the British Empire, and in 1788 he was in Halifax, Nova Scotia with Miriam. He and Miriam hosted Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, a younger brother of George III who had joined the army. When Miriam and Abraham’s second son was born in Halifax, the prince was the child’s godfather, and was named after him.[12]Baptism: Barbados Mercury 23 December 1788.

Abraham died in 1806, aged only 47, in an accident involving a cart. He was buried in Ringmer, East Sussex, and the church still has a memorial on the wall to him. Featuring cannon and flags, it is a suitably militaristic memorial for the soldier. Abraham and Miriam had ten children, and with some of them still quite young at the time of their father’s death, Miriam was extremely lucky that she was a friend of the royal family. Prince William Henry stepped in, giving commissions to her sons.[13]Information on the Du Vernets from The Story of Radio Mind: A Missionary’s Journey on Indigenous Land by Pamela E. Klassen, University of Chicago Press, 2018, and the Dictionary of Canadian … Continue reading The links with the royals didn’t end there – when Miriam wrote her very short will in 1839, it solely concerned the fate of “the large silver waiter sent to me by his late Majesty William the 4th.”[14]Prerogative Court of Canterbury will of Miriam Du Vernet Grossett Muirhead, Widow of Bredisholm, Lanarkshire, and Stonehouse, Devon. PROB 11/1961/174

Miriam’s links with the royals explains the patronage which Mary Ann received. She dedicated Sketches of Life and Manners to the Princess of Wales, who in 1811 was the popular Caroline of Brunswick. That same year, in 1811, Caroline’s (unpopular) husband would become the Prince Regent. The Princess of Wales’ name tops the list of Mary Ann’s subscribers, followed by Caroline’s uncle – His Royal Highness the Duke of Gloucester (who bought not one, but two copies), or in other words, a friend of Mary Ann’s step-sister.

While Miriam may have arranged for Mary Ann to receive royal patronage for Sketches, intriguingly there’s no Golls, Grossetts, Muirheads or Du Vernets among the subscribers.

There is whole other story about Miriam which I won’t go into in huge detail here as this is Mary Ann’s biography, but a quick note anyway: Miriam inherited Bredisholm, the estate just outside Coatbridge in Lanarkshire that had once belonged to her maternal grandparents, as her brother, John Henry Goll, had disappeared.[15]Several adverts were placed in the press in 1813 searching for him. eg. Morning Advertiser, 20 September 1836: “Mr John Goll, a Midshipsman in the Royal Navy, and son of Colonel John Goll, of … Continue reading She changed her name to Miriam Du Vernet Grossett Muirhead.

And what of Colonel G? As we know from Mary Ann’s letters, she had arrived in Fort George by December 1795, after a horrendous journey by sea, which would’ve been a few months after Goll joined the Invalid Regiment. Mary Ann’s letters are all written from Fort George, until December 1798, when she writes to Miss Eliza G from London. She didn’t see Goll again. He stayed at Fort George, which is where he wrote his will on 13th April 1799. He died the following day. Mary Ann described his death as “sudden and unexpected.”[16]Letter XIV, Hermitage, North End, May 1799, p126-131 In his will, he left a third of his of “effects” to his wife Mrs Elizabeth Ann Goll, and the remaining two-thirds to be divided among three of his children: John Alexander Goll, Miriam, Louisa Sproul, and Rosamond Goll.

Interestingly, Louisa is mentioned in Mary Ann’s letter: “My poor dear mother must have endured a great deal of fatigue in dealing on him and poor Louisa”, and “Louisa has arrived safe in England, with her little boy, and is now lying I fear on her deathbed.” And in his will, Goll directed that money was to be deducted for “the necessary expenses of bringing from and returning to London from this place my foresaid daughter Mrs Sproul.” Louisa Charlotte Goll had married Robert Sproul at St James’, Piccadilly, in 1792, and their son Leonard Morse Sproul was born in 1795. Presumably he is the little boy who Mary Anne mentions.

Lieutenant Colonel John Daniel Goll was buried at Kirkton of Ardersier in Inverness-shire, where his memorial slab can still be seen.[17]Transcription from Scotland Memorial Inscriptions on FindMyPast, copyright the Highland Family History Society. It reads:

Sacred to the memory of Lieutt Coll John Danl Goll, Captain in the Royal Regt of Artillery, who after faithfully serving his King & Country 45 years, departed this life at Fort George the 14th day of April AD 1799 in the 67th year of his age.

As we know from the letters, in summer 1800 Mary Ann went to Botesdale in Suffolk to visit her cousin Mr H (or, as we now know him, Reverend William Hepworth). Then, in January 1801, she wrote from Charles Street, Queens Elm, in Chelsea, to say that her mother had died.[18]Letter XXI, p176-182 This is where some unsolved mysteries creep in. Exactly when Ann Elizabeth died is unclear. The last letter from Botesdale was written in October 1800, and a letter is omitted which Mary Ann wrote to her friend Miss Charlotte D. where she told her she was settled in London with her mother, and a cousin also called Mary Anne. So Ann Elizabeth presumably died between November 1800 and January 1801, but I haven’t found a burial for her in London, Suffolk, or West Yorkshire. London seems the most likely place for her burial, though, as aside from the fact that generally people were buried near to where they died, Mary Ann’s letter mentions that “my kind and respected friend Mrs A. conveyed me the sad evening of my mother’s funeral to her house.”

And then there is Mary Ann’s cousin Mary Ann. There’s no initial letter for her surname. As she’s mentioned in the last letter Mary Anne wrote from Botesdale, I had assumed that she’s Reverend William Hepworth’s daughter, but I can’t find any evidence that he had a daughter. Of course, she could have been another Hepworth relative who was staying in Botesdale at the same time as Mary Ann. She might not even have been on Mary Ann’s mother’s side anyway, and was instead on the Nicholson side – could she have been a daughter of Mary Ann’s paternal aunt, Elizabeth Turner?

After Sketches

The last letter in the last volume of Sketches is dated June 1808, from Sluggan, Inverness-shire, where Mary Ann was living with her husband James Grant. Three years later, the first edition of Sketches would be published. But Mary Ann’s story doesn’t finish in Scotland – and neither does the story of her husband.

At the end of Mary Ann’s second book, Tales Founded on Facts, published in 1820, there is an advert for a school in Park House, Croydon: “Mrs Grant’s Establishment for the Education of Young Ladies.” I had wondered if this was Mary Ann’s school, unless she was giving advertising space to one of the Grant clan (the Grants had, after all, filled the subscriber list in Sketches). At the end of the advert, we’re told that “Terms etc” can be had from Messrs. Boosey and Sons – who published Tales, which does suggest it was Mary Ann’s school. J. Rees, a Bristol bookseller, put an advert for Tales in the Bristol Mirror on 31st March 1821, stating that the author was “Mrs Grant of Croydon”. This is tantalising as it does very much look like it was indeed Mary Ann who was behind the Park House school, however, it might just mean that Rees, like me, had assumed that Mary Ann Grant the author and Mrs Grant the teacher were one and the same person.

The advert which appeared in Tales also appeared in The Edinburgh Review in 1820, with the terms. Full board was 60 guineas, but “additional accomplishments in MUSIC and DANCING” would cost 75 guineas instead, and anyone requiring extras such as globes and velvet painting would need to stump up 100 guineas. Staying at the school over the vacations would cost 5 guineas. The advert concludes “parlour boarders received.” For anyone curious, Harriet Smith in Emma is a parlour boarder, having finished her schooling but stays on as a lodger. In other examples I’ve found, a parlour boarder might occasionally give lessons as well, so they are similar too but not identical to a pupil-teacher.

Unfortunately, a writer called William Watts must’ve read that particular issue of The Edinburgh Review, as he referred to the advert in his long poem The Yahoo. As a footnote, he refers to the advert as “pompous”, full of “frothy stuff.” It must be said that Mary Ann wasn’t averse to purple prose…

We can see from the letters Mary Ann wrote from Sluggan that she hadn’t got into the swing of living in the Highlands. She was trying her best to be positive about life in Sluggan, and she was meeting local Grants in the area (there were rather a lot of them), but it sounds, reading between the lines, as if she was on her own at home quite a lot, while James went off to enjoy the hunting and fishing in the area. So leaving the Highlands for Surrey, in order to set up a school, does sound entirely plausible.

In about 1822, the couple moved to Teignmouth in Devon, nearly 600 miles from Sluggan.[19]James’ obituary in 1829 says he was “nearly seven years resident of Teignmouth, Devonshire”: Sherbourne Mercury, 18th May 1829 Again, we don’t know why. Perhaps Park House school hadn’t worked and the Grants decided to retire, or set up a school in Devon instead. There was another Major Grant, who had been in the Royal Invalids, and his wife living in Teignmouth in the 1820s – in 1828, Major Grant’s wife had a son.[20]Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 20 September 1828. A birth announcement for the son of Major Grant and his wife, of Garden Cottage, Teignmouth Hill, born on 14th September. A Major Grant, dressing as a … Continue reading The fact that there was another Major Grant in the same town in Devon suggests that it might be one of James’ relatives.

Then in 1829, James fell ill, either on a visit to London, or perhaps in Devon so he had gone to London to seek treatment. He was tended to by Dr George Pearse, who had been Lord Nelson’s surgeon on board the San Josef.[21]Obituary of Dr William Edwin Grindley Pearse, the BMJ, 20th June 1891, p.1363, provides this fact about Dr George Pearse. His son, Dr William Edwin Grindley Pearse, was one of the Mary Ann’s … Continue reading James was buried at St Clement Danes on the Strand on 13th April 1829, his address given as 2 Thanet Place, which was in the parish. A month later, a death announcement was placed in the Sherbourne Mercury and the Morning Herald:

After a few weeks illness, at 2, Thanet-place, Temple Bar, Strand, James Grant Esq, late Major 42d Royal Highlanders, aged 64 years, nearly seven years resident of Teignmouth, Devonshire.

He doesn’t appear to have left a will, and I can’t find him in the Death Duty Index, which includes people who died intestate as well. And confusingly, while the newspaper announcements say that James was 64, the St Clement Danes’ burial register says he 68.

Life in Devon

Mary Ann would spend the rest of her long life in Plymouth, Devon. She appears in the records again in 1841 on the census, where she was living in Plymouth, Devon, nearly forty miles from Teignmouth, at Wyndham Place with a servant. Then in 1851, she was living at 4 Summerland Place, as a lodger in the home of Elizabeth Key. Her place of birth is given as “Battle Bridge” in Middlesex: “Gray’s Inn Road, the New Road, Old St Pancras Road and Maiden Lane all converged on Battle Bridge, for long a transport hub, where a broad ford crossed the River Fleet.”[22]Camden Railway Heritage Trust In 1861 she was a lodger in the home of Thomas Pike, a clerk in an omnibus office, and there was one other lodger too: a 30-year-old comedian called William Warboys, “a fine low comedian from the Old Vic”.[23]The Referee 17 January 1909. The writer refers to a production he saw of Charles Reade’s The Robust Invalid, a version of La Malade Imaginaire, performed at the Adelphi in 1870. The cast … Continue reading I would dearly love to know how – and in fact, if – Mary Ann and the comedian got along. They had both been born in London, though, so they at least had that in common.

In the absence of any known letters or diaries by Mary Ann, the later years of her life can only be hinted at by her will. She wrote it in early 1868, and it doesn’t mention any of her relatives. Her executors were George Pearse and William Grindley Pearse (or William Edwin Grindley Pearse as he was known), and she left them £40 each “as an acknowledgement for their late father’s attention to my late husband Major Grant in 1829”. The children of George and William’s sister Catherine Cooper were to have £25 shared between them. It’s not clear if Mary Ann and James had known the Pearses before James’ illness, or if they became Mary Ann’s friends after James’ death. She left £5 to Frederick Pearse Jago, “as an acknowledgement for his kind attendance to me during my last illness.” Frederick was born in Bodmin in 1817, and baptised as Frederic William Pearce Jago.[24]TNA/RG/5/162, Bodmin Wesleyan Methodist baptism record. Frederic was presumably related to Mary Ann’s executors.

Then there are Mary Ann’s friends who were left legacies: Mrs Frances Fricker senior of Denmark House, Poole in Dorset was left £15 “in remembrance of old friendship”. Miss Silvia Lott of Wenkworth Villa in Mannamead, Plymouth was left £10, and Mrs Jane Plummer of Park Hill Crescent in Plymouth, another of Mary Anne’s friends, was left £5.

Miss Hannah Blake of 332 Grays Inn Road was left £12. I had initially hoped she would be the Miss Hannah B who Mary Anne wrote some of her letters to. However, it seems that she was a governess, born in 1803, so she might have known Mary Ann through the school in Croydon. Hannah’s family lived in St Pancras, so it might even be the case that Mary Ann knew her from her days in London – even though Mary Ann had left St Pancras by the time Hannah was born. As an aside, Hannah’s grandfather was coalheaver-turned-Independent preacher William Huntington, who wrote his own memorial inscription in which he rather pompously declared he was “beloved of his God but abhorred of men. The omniscient Judge at the grand assize shall ratify and confirm this to the confusion of many thousands, for England and its metropolis will know that there has been a prophet amongst them.” Hannah’s father was a currier, but her grandfather made a lot of money through preaching and after his first wife died in 1806, he married Lady Elizabeth Sanderson, the widow of a baronet and former Lord Mayor of London.

Several charitable causes were close to Mary Ann’s heart. The first tells us about her religious affiliation – she left £30 to Plymouth’s Unitarian chapel for either a jug for the communion table, or to be given “for the benefit of the poor” of the chapel. She left £10 for the Midnight Meeting on Euston Road – what we might now call a Christian outreach organisation for sex workers. Mary Ann left £15 for the New Orphan Asylum in Ashley Down, Bristol – as someone who had lost her father before she was ten, and who had lost two stepfathers and her own mother before she was twenty, we can see why she had sympathy for children left destitute by the deaths of their parents. Mary Ann was fortunate that her family was well-to-do so that she hadn’t needed to seek the help of charity. And last but not least, Mary Ann left £3 to the Plymouth branch of the Society of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the forerunning of the RSPCA.

The end

Mary Ann Grant died on 27th December 1869 at 6 Glanville Street, Plymouth. Her death certificate describes her as “the widow of Major James Grant.” She was 88-years-old, and her cause of death is given as “old age.” It appears that Mary Ann was living at another lodging house as her death was registered by Samuel Mumford of the same address, and on the censuses he’s a lodging house keeper. A death notice was placed in the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette.[25]29th and 31st December 1869. Her age is given as 89.

I wondered where Mary Ann Grant was buried, but it isn’t an easy question to answer. The most obvious place would be Ford Park cemetery in Plymouth, which opened in 1848. But there’s no record of her burial there. Bearing in mind how she lived in many places in Britain over her long life, never entirely settled until her later years, it seems rather fitting that her last resting place remains – for now – unknown.

My thanks to Rosemary Wake who contacted me about Mary Anne Grant, which prompted me to look again and see if I could discover anything more about her. Rosemary is researching another Mrs Grant, who wrote Popular Models.

First published: 11th July 2022.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Perkins, P. “The Travels of Elizabeth Isabella Spence”, The Bottle Imp, 11, May 2012 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Hopper, G., ed., The Tourist’s Gaze: Travellers to Ireland, 1800-2000, Cork: Cork University Press, 2001. p. 13 |

| ↑3 | Prerogative Court of Canterbury will of the Reverend William Hepworth of Botesdale, Suffolk: PROB 11/1947/125 |

| ↑4 | LMA archive. |

| ↑5 | His Prerogative Court of Canterbury will says he was a victualler of Poland Street, near Oxford Street, and Ed Pope’s notes on Poland Street show Robert Nicholson on that street at the Pantheon Punch House from 1787-1798. |

| ↑6 | When I bought some trousers and a sunhat at that particular M&S, I had no idea it had once been the site of such an amazing building! |

| ↑7 | When he died that year is unclear, as I haven’t found his burial. He wrote his will on 22nd January 1789, and it was probated on 4th September the same year. There is a possible burial at Whitefield’s in Camden in June 1789 of Robert Nicholson of St George’s, aged 47. However, the administration note written in the margin in 1809 says that Robert was of St James’ Westminster. PCC will, PROB 11/1183/90 |

| ↑8 | He was buried at St Andrew’s, Holborn, on 7th February |

| ↑9 | Presumably it was called “Old Christmas” because it’s where Christmas would’ve fallen if not for calendar reforms in the eighteenth century. |

| ↑10 | Sources: the Army List and “Royal Artillery Officers, 1716-1899” on FindMyPast. |

| ↑11 | Information on Margaret’s family drawn from Mother Bedford. |

| ↑12 | Baptism: Barbados Mercury 23 December 1788. |

| ↑13 | Information on the Du Vernets from The Story of Radio Mind: A Missionary’s Journey on Indigenous Land by Pamela E. Klassen, University of Chicago Press, 2018, and the Dictionary of Canadian Biography entry on Henry Abraham Du Vernet, one of Miriam and Abraham’s sons. |

| ↑14 | Prerogative Court of Canterbury will of Miriam Du Vernet Grossett Muirhead, Widow of Bredisholm, Lanarkshire, and Stonehouse, Devon. PROB 11/1961/174 |

| ↑15 | Several adverts were placed in the press in 1813 searching for him. eg. Morning Advertiser, 20 September 1836: “Mr John Goll, a Midshipsman in the Royal Navy, and son of Colonel John Goll, of the Royal Artillery. If the above-named gentleman be alive, or have left any descendant, he is requested to apply immediately to Messrs. Lyon, Barnes, and Ellis, No 7, Spring-gardens, London, who will give him information greatly to his advantage. Mr. Goll is supposed to have married a Miss Stuart, and in the year 1813 to have been occasionally employed by Messrs. Ackerman of the Strand, when he resided in the vicinity of Lambeth-terrace. Any person who will give satisfactory information of Mr. Goll, or of the time of his death, shall receive a REWARD of TEN GUINEAS.” I found the marriage of John Alexander Goll of Fulham, and Charlotte Steward in 1786 at St Anne’s, Soho, and baptisms of three children in the 1790s (Charles born 1792, William born 1795, Charlotte born 1799), although the mother’s name was Henrietta – either a second wife, or perhaps his wife was also known as Charlotte Henrietta or the reverse. The children’s baptisms are in different places around London – William baptised at Christchurch, Surrey, Charles at St Giles’, Cripplegate, and Charlotte at St Margaret’s, Westminster. Charles’ baptisms tells us that John was a picture frame maker. Rudolph Ackermann was a printer and bookseller who was based at no. 101 Strand from 1794. Reference: Britain Express. There is a burial at St Mary’s Lambeth in 1805 for Charlotte Goll of Oakley Street, but I haven’t been able to trace John Alexander Goll and his family any further. No ten guinea reward for me! I assume the following reward has now rather lapsed: Morning Advertiser, 26 November 1836, “To parish clerks – one guinea reward, and the usual Fees, will be paid on the production of a CERTIFICATE of the MARRIAGE of JOHN ALEXANDER GOLL (or John Goll) with CHARLOTTE STEWARD. The marriage took place in one of the metropolitan parishes, or in the environs of London, between 1780 and 1791. Apply to Lyon, Barnes, and Ellis, of No. 7, Spring-gardens.” |

| ↑16 | Letter XIV, Hermitage, North End, May 1799, p126-131 |

| ↑17 | Transcription from Scotland Memorial Inscriptions on FindMyPast, copyright the Highland Family History Society. |

| ↑18 | Letter XXI, p176-182 |

| ↑19 | James’ obituary in 1829 says he was “nearly seven years resident of Teignmouth, Devonshire”: Sherbourne Mercury, 18th May 1829 |

| ↑20 | Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 20 September 1828. A birth announcement for the son of Major Grant and his wife, of Garden Cottage, Teignmouth Hill, born on 14th September. A Major Grant, dressing as a Highlander, attended a fancy dress ball that same month – I have no way of knowing which Major Grant it was. There is a baptism in 1821 at West Teignmouth of Eliza Jennette, daughter of James Grant esq and his wife Eliza Jennette. The couple married at Marylebone in 1817, but I don’t know anything more about them. |

| ↑21 | Obituary of Dr William Edwin Grindley Pearse, the BMJ, 20th June 1891, p.1363, provides this fact about Dr George Pearse. His son, Dr William Edwin Grindley Pearse, was one of the Mary Ann’s executors, as you will see below. |

| ↑22 | Camden Railway Heritage Trust |

| ↑23 | The Referee 17 January 1909. The writer refers to a production he saw of Charles Reade’s The Robust Invalid, a version of La Malade Imaginaire, performed at the Adelphi in 1870. The cast included, as well as Mary Ann’s erstwhile fellow-lodger, 16-year-old Florence Terry, sister of “Ellen, Kate, Marion and Fred Terry.” |

| ↑24 | TNA/RG/5/162, Bodmin Wesleyan Methodist baptism record. |

| ↑25 | 29th and 31st December 1869. Her age is given as 89. |