The “Plowman,” The Old Farmer’s Almanac’s, 1794.

Elizabeth Wade was the third child of Edward WadeI and his wife Elizabeth Cardinal. She was baptised in Layer-de-la-Haye on 17th February 1771. She presumably moved with the family to Polstead in Suffolk, where her two younger brothers, Thomas and Samuel, were baptised in 1776 and 1778. But by 1790 at the latest, the Wade family was back in Essex, this time living in Fingringhoe, and it was on 3rd December 1790 that the nineteen year old Elizabeth married Thomas Lewis Stone. One of the witnesses was William Wade – presumably Elizabeth’s brother, William Cardinal Wade.

Thomas Lewis Stone

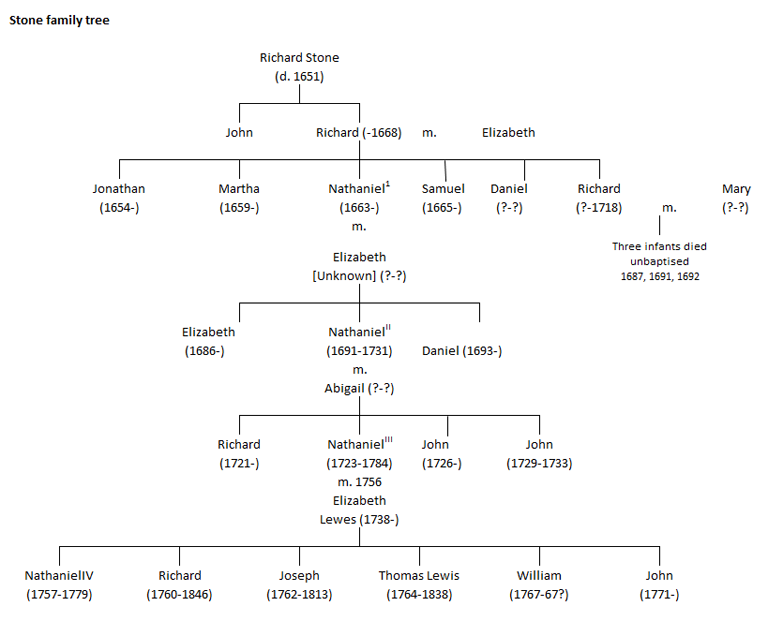

Thomas was baptised in Fingringhoe on 15th April 1764, the son of Nathaniel StoneIII and Elizabeth (née Lewis). The spelling of “Lewis” does vary a little – Thomas spelt it “Lewes” when he married Elizabeth Wade, but later generations spelt it “Lewis”, and it is sometimes spelt in registers as “Lues”. Nathaniel and Elizabeth had six sons, baptised at Fingringhoe:

- NathanielIV, 29th May 1757 (possibly died 1779)

- Richard, 3rd February 1760 (died 1846)

- Joseph, 24th January 1762 (died 1813)

- Thomas Lewis, 15th April 1764

- William, 21st June 1767

- John, 14th April 1771

The Stones are very much a Fingringhoe family – Thomas’ line can be traced back to the earliest entries in the parish register in the 1650s, and there are wills for members of the Stone family which go back another century, to the 1550s. The 1651 will of Richard Stone of Fingringhoe mentions his two sons, John and Richard, and in the 1650s and 1660s, Richard (perhaps the son in the 1650 will) and Elizabeth Stone’s children were baptised in Fingringhoe. There are four in the register (Jonathan 1654, Martha 1659, NathanielI 1663, Samuel 1665) although Richard’s 1668 will mentions a further two more children, Richard and Daniel. Richard senior left his property to his wife, and on her death, it was to go to Richard and Jonathan.[1]After his mothers’s death, Richard was to inherit a messuage and land called Michels and land called East Donstalls, both in Fingringhoe, as long as he gave the four youngest children £60 … Continue reading Richard junior died in May 1718 in Fingringhoe, and appears to have had no children. In his will,[2]Richard is no doubt the son of Richard and Elizabeth who was to inherit Michels and Donstalls on his mother’s death (see footnote 1 above). Michels had been in the Stone family some time … Continue reading his wife Mary was to inherit all his land, but on her decease, it was to go to “my nephew Nathaniell StoneII, son of my late brother Nathaniell StoneI, deceased.” There are baptisms for three children of Richard junior’s brother, NathanielI, in the Fingringhoe register (Elizabeth 1686, Nathaniel 1691II, Daniel 1693). It is presumably Nathaniel, born about 1691, who was Richard junior’s heir.

NathanielII and his wife, Abigail, baptised four sons at Fingringhoe (Richard 1721, NathanielIII 1723, John 1726, John 1729), and he died in 1731. It was the third Nathaniel Stone who married Elizabeth Lewes in 1756 and was Thomas Lewis Stone’s father.

Click to enlarge

Nathaniel Stone

On his marriage, NathanielIII‘s occupation, farmer, appeared in the register. One of the witnesses was Thomas Lewes – this is probably Elizabeth Lewis’ father: she was baptised in Fingringhoe on 5th March 1738, daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth.[3]In all there are four baptisms in the Fingringhoe register for Elizabeth, daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth Lewes at this period: 24th April 1726 (buried 22nd Dec 1730), 19th Dec 1731 (buried 15th … Continue reading Her father, died in 1777 – there is a gap in the Fingringhoe register, missing out 1777 entirely, but he left a will, written in February 1777 and proved in June the same year. Another Thomas Lewes was buried in Fingringhoe in 1762, who may have been Elizabeth’s brother, born about 1724. Thomas’ 1777 will[4]ERO ref: D/ABW 106/1/42. This will also mentions a granddaughter called Elizabeth Lewes – she may be the daughter of Thomas junior or Joseph – her parents aren’t mentioned in the … Continue reading leaves all his copyhold to his grandson Nathaniel StoneIV, and in the event of his death without a male heir, a farm to his grandson Joseph Stone and another to Thomas Lewes Stone. NathanielIV did indeed die without issue, so his brother Joseph and Thomas Lewes Stone inherited their grandfather’s farms and land.

ERO holds a rather curious object, which belonged to a Nathaniel Stone: “Continuous passages of verse, mainly religious, brief notes on weather, and lists of preachers with texts and dates of sermons [churches inc. Fingringhoe, Wivenhoe, and E. Donyland]. At end: farm accounts, 1782 (1p.)”.[5]ERO ref: D/DU 251/88. Another item to look at on my next archival rummage…. This particular Nathaniel died in 1784, but I’m not sure if this was Thomas Lewis Stone’s fatherIII or his brotherIV, though it is most likely to be Nathaniel StoneIII. There are burials in Fingringhoe for a Nathaniel Stone in 1779 and 1784 – the first may have been Thomas Lewis Stone’s brother, and the second his father, but the burial register gives no information apart from the name and the date, so it’s impossible to say for sure.

Richard Stone

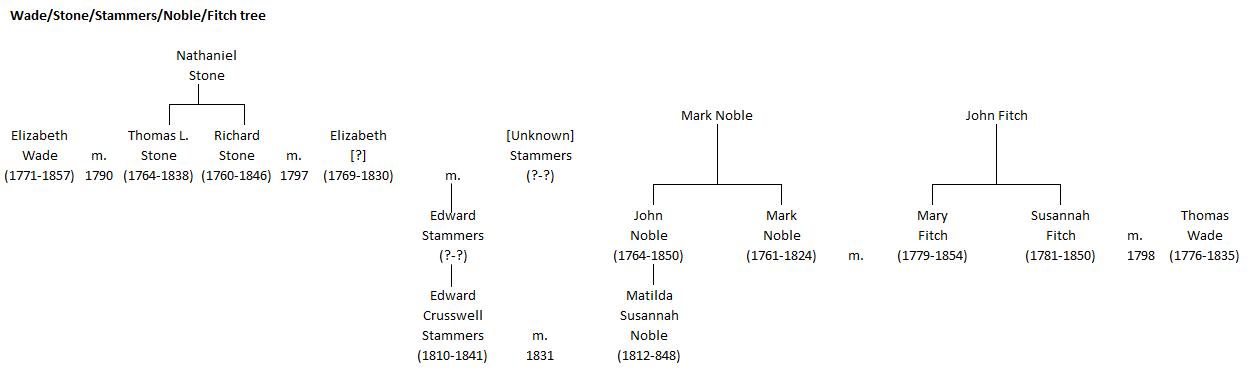

By the time Thomas Lewis Stone married Elizabeth Wade in 1790, his father and his eldest brother were dead. He was the second eldest surviving brother – Richard, the eldest, moved to Colchester at some point, but was still in Fingringhoe at this time. In 1794, Richard’s illegitimate child by Rose Moore, Nathaniel, was born, and in 1797, Richard married Elizabeth Stammers, a widow. The Stammers family were the millers in Fingringhoe. Elizabeth’s child, Edward, by her first husband, had a son called Edward Cruswell Stammers. He married Matilda Susannah Noble, from Brightlingsea, and in one of those confusing connections which seem to be the hallmark of anyone appearing in this story, Matilda was in fact related to the Wades as well (as the tree below attempts to demonstrate). Her uncle, Mark Noble, was married to Mary Fitch, and Mary’s sister, Susannah, married Thomas Wade (1776-1835) – a son of Edward Wade and Elizabeth (née Cardinal). One wonders, as usual, whether this was by design or coincidence.

Click to enlarge

When Richard’s wife died in 1830, she was buried in Fingringhoe, but her abode in the burial register is East Donyland, and when Richard himself died in 1846, he was also buried in Fingringhoe, and his abode was Colchester. Some of Thomas Lewis Stone’s children had moved to Colchester by this time, so that might be why he was living there. Richard and Elizabeth had one son, Richard Nathaniel, in 1798, and he died in 1840.

The Cardinal/Wade connection – again

Another interesting object at ERO can be found in the farming records for Fingringhoe, which pertain to the payment of rent by Thomas Lewis Stone to Clarkson Cardinall.[6]ERO ref: D/DU 251/94A. As above…. Now, Clarkson, you may recall, lived in Tendring, and might be a relative of Elizabeth Cardinal, hence it could explain why William Cardinal Wade lived in Tendring too. These farming records at ERO date from 1793-1807 – perhaps Thomas became Clarkson’s tenant after his marriage to Elizabeth, or maybe he had been his tenant earlier and those records don’t survive: at any rate, it gives us another link between the Wades and the Cardinal family at Tendring.

Their children

Thomas and Elizabeth Stone’s twelve children were born and baptised over a period of 20 years at Fingringhoe:

- Thomas Lewis Nathaniel, b. 18th Jan 1791, bap. 9th Feb 1791

- Richard Edward, b. 8th Dec 1791, bap. 1st Jan 1792

- Sophia Elizabeth, b. 20th May 1793, bap. 4th Oct 1795

- Joseph, b. 11th Jan 1795, bap. the same day as Sophia. He never married and died in Fingringhoe in 1888, at the age of 93.

- Sarah Whittaker, b. 26th May 1796, bap. 4th March 1798. Died 1809.

- William Henry, b. 19th Jan 1798, bap. the same day as Sarah.

- Elizabeth, b. 24th Sep 1803, bap. 20th Sep 1807

- Henrietta, b. 25th May 1804, bap. ditto. Died 1810.

- Charles, b. 13 Jun 1805, bap. ditto.

- Philip, b. 27 Feb 1807, bap. ditto.

- Charlotte Eliza, b. 15 Aug 1808, bap. 28th April 1811. Died 1827.

- Hermon Whittaker, b. 05 Nov 1810, bap. ditto. Died 1811.

The Adventure of the Stolen Turnips

It would appear that Thomas Lewis Stone farmed quite happily in Fingringhoe, and although he didn’t leave a will, some of his sons continued to farm in the same village, perhaps inheriting his land by default. There is a newspaper story in the Chelmsford Chronicle on 30th December 1836, where a Thomas Lewis Stone of Fingringhoe went to the magistrates on Christmas Eve at Colchester Castle, over his turnips being stolen. One can’t tell from the newspaper story if it was Thomas Lewis Stone senior (who would have been 72 at the time) or junior (who would have been 45 – he dropped the ‘Nathaniel’ from his name by the time of his marriage in 1816) who was the complainant in this sorry tale of rural skulduggery, but he was clearly fed up with his crops being stolen.

TURNIP STEALING – Mary Austin, Sarah Hadleigh, and a little girl named Eliza Crosby, were charged with stealing a quantity of turnips, the property of Thomas Lewis Stone, of Fingringhoe. Mr. Stone, brother to the prosecutor, stated, that within the last fortnight his brother had severely suffered from robberies of this description, therefore he was determined to punish the first that could be detected, as an example to others. On Tuesday morning last he (witness) saw the prisoners leaving his brother’s turnip field, with about a bushel of Swedish turnips in their possession; he stopped them and took away the turnips. The prisoners all admitted their guilt. The prisoner Crosby was brought up on a similar charge a few weeks ago, but the Bench having ascertained that she was induced to commit the robbery by a woman named Baker, they did not proceed to a conviction on account of her tender age, and she was admonished and discharged, but the admonition and leniency of the Bench seemed to have had no beneficial effect upon her. They were all convicted and sentenced to pay a penalty of 5s. each and expences, and in default were committed for 14 days to the House of Correction.

Eliza Crosby is probably the Eliza, daughter of John and Susannah Crossby, who was baptised in Fingringhoe in 1823, so she would have been about 13 at the time of the turnip theft – although whether this qualifies her to be referred to as “a little girl” is hard to say. I have been unable to find mention of her earlier crime in the newspapers – there was a Baker family in Fingringhoe at this time, so it is perhaps in connection with them. There was a Sarah Hadley baptised in Fingringhoe in 1825, who would have been 11 at the time, but her mother was called Sarah as well, so equally it could be her. There are also several people by the name of Austin in Fingringhoe at the time, so this was a theft carried out by locals against a local farmer. But consider the social problems of the time – two years before this theft, the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act was passed, which made life harder for the poor. It was unpopular and historians now see it as cruel and inhumane. And bear in mind that Karl Marx included Fingringhoe in Das Kapital:

In this county [Essex], diminutions in the number of persons and of cottages go, in many parishes, hand in hand. In not less than 22 parishes, however, the destruction of houses has not prevented increase of population, or has not brought about that expulsion which, under the name “migration to towns,” generally occurs. In Fingringhoe, a parish of 3,443 acres, were in 1851, 145 houses; in 1861, only 110. But the people did not wish to go away, and managed even to increase under these circumstances. In 1851, 252 persons inhabited 61 houses, but in 1861, 262 persons were squeezed into 49 houses.[7]Karl Marx, Das Kapital, Chapter 25: “The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation”.

This gives us a disturbing snapshot of what was happening in these villages. Whilst the Wades left Fingringhoe for East Donyland in the 1830s and 1840s, many people remained, even though living standards fell, if Marx’s figures give an indication. His figures yield about four people per house in 1851 and five per house in 1861, and while this increase might seem slight, and could be put down to increased family sizes, we need to combine it with the “Hungry 40s” and the cruelty of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act to gain a better picture of what was happening. Quite often, when you look through the censuses, you see extended family members living together, and it is quite possible people were living that way to avoid the dreaded Workhouse. Marx, it seems, saw the reduction of houses and the increase of population as a sign of general want and poverty, money disappearing from the hands of ordinary people and into the pockets of the rich. While the turnip theft occurred before the period Marx refers to, it is indicative of the rural environment of that period which our ancestors lived through. So whilst we might laugh about Thomas Lewis Stone losing his rag about his turnips being nicked, it’s important to consider the fact that the locals, even youngsters, were stealing food – perhaps not for merry japes or base delinquency, but for the simple reason that they were poor and hungry.

It’s not necessarily the case that the Stone family benefited hugely at the expense of their labourers – in 1851, William Stone (born 1798) was farming 248 acres in Fingringhoe, which is about 7% of the parish’s total area. He employed five labourers. When Thomas Lewis Stone went to the magistrate, he was defending his profit margins, but if his income suffered, it would affect his ability to employ the men who worked on his land with him. Farmers were forever at the whim of markets, bad weather and crop diseases, so had to take a stand against theft. We don’t know how involved the Stone family were in the village’s charitable endeavours – did they help set up a ragged school and distribute alms? And consider too that thirty years earlier, although he had inherited property from his grandfather, Thomas Lewis Stone was renting his farm from Clarkson Cardinall: those 248 acres farmed by William Stone may not have been owned by him.

A rather old lady

Thomas Lewis Stone died in 1838, at the age of 74. He didn’t leave a will and (as far as I can tell) doesn’t appear in the Death Duty registers. There don’t appear to be any surviving memorial inscriptions in Fingringhoe churchyard for members of the Stone family. He passed away two years before a very sad year for both the Stone and Wade families – in 1840, Thomas and Elizabeth’s son Philip was killed in tragic circumstances, and Charles Whittaker Wade, Elizabeth’s nephew, lost two of his young sons in an accident.

Elizabeth is one of only two of Edward and Elizabeth Wade’s children to live until the 1841 and 1851 censuses. In 1841, Elizabeth appears on the census aged 70, of “independent means” (perhaps she and her husband had provided annuities for themselves, or something was arranged to provide for her from his estate after his death). She lives with James Stone, a 68 year old agricultural labourer (whom I am yet to identify – a brother of Thomas Lewis Stone whose baptism I haven’t found? Perhaps her husband’s cousin?), her son William, a 40-year old farmer, and another of her sons, Joseph, aged 43, an agricultural labourer. The fact that two of the men in the household were labourers suggests that they were not one of the wealthier farming families – their money came not through income from land, but from their own work. The 1841 census can be a bit tricky, as it doesn’t give people’s relationships to each other. It seems that in the Stone’s house, but not of their family, was someone called Amelia Horne, a 30-year old of independent means. Who was she? Again, she is someone I am yet to identify.

On the 1851 census, Elizabeth is 80, her place of birth given as Layer. The head of the household is her son William, 53, “farmer 89 acres arable grass 159 acres employing 5 labourer.” After the census was taken in 1841, he had married Anna Amelia Malom, who had been born in Bungay, Suffolk, in 1808 (Anna is probably the sister of Mary Malom, who married William’s brother, Charles Stone). Also in the household is Elizabeth’s son Joseph, aged 56. Joseph’s occupation isn’t given – he appears only as “farmer’s brother”. Perhaps this implied his occupation, although he had been an agricultural labourer on the 1841 census so maybe he helped his brother on the farm. It is slightly strange that his younger brother was the farmer, whereas the older Joseph wasn’t. No disability is given for him on the census, and Joseph lived to be 93, but perhaps there was some reason why he wasn’t able to take on the responsibility of running a farm, unlike his brother. Another member of their household on the census is 8-year old Emma Rivers, her relationship being only “visitor”, who was born in Essex Road, London. She is another person I am yet to identify – in the 1861 census, she is living in Fingringhoe with John Bateman, a 64 year old hairdresser born in Little Clacton, as his niece. Joseph Stone, 66, is also living with John Bateman – his relationship given as “brother” – this, then, is another mystery to be solved.

When Elizabeth died in December 1857, she was 86. She had had twelve children and was the grandmother of thirty-two grandchildren. She was also great-aunt of some of her grand-children: her son, Thomas Lewis Nathaniel Wade, married her niece Susannah Wade (daughter of William Cardinal Wade), and her daughter Sophia Elizabeth married her nephew Edward Pritchett Wade (son of another of Elizabeth’s brothers, Edward Wade). By marrying Thomas Lewis Stone, Elizabeth Wade had become part of an old Fingringhoe family, and was instrumental in making that family larger. When her son William was buried in Fingringhoe in 1892, aged 94, there is a note in the register saying “Last of family” – he was the last one in Fingringhoe, but the others had gone further afield, to Colchester, Wivenhoe and even Nottinghamshire.

As with all these histories, imposing an ending on it by finishing at these characters’ deaths seems rather false: in many ways, their stories never end. What became of Elizabeth’s many children will be explored in later pieces.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | After his mothers’s death, Richard was to inherit a messuage and land called Michels and land called East Donstalls, both in Fingringhoe, as long as he gave the four youngest children £60 each: those children being Daniel, Martha, Nathaniel and Samuel. John (presumably Jonathan, born in 1654) was to inherit land called Brookshalls after his mother’s death. One of the witnesses was John Stone senior. ERO ref: D/ABW 65/109. The 1651 will of Richard Stone senior leaves a “copyhold tenement called Mychels” to his son, Richard. ERO ref: D/ACW 15/316 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Richard is no doubt the son of Richard and Elizabeth who was to inherit Michels and Donstalls on his mother’s death (see footnote 1 above). Michels had been in the Stone family some time – it is mentioned in the 1591/2 will of John Stone (ERO ref: D/ABW 35/112). Richard senior mentions Henry Spurham, “son of my sister Martha Firmin, now wife of Thomas Firmin” – Nathaniel was only to inherit his uncle’s property on his aunt’s death as long as he gave Henry £200. |

| ↑3 | In all there are four baptisms in the Fingringhoe register for Elizabeth, daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth Lewes at this period: 24th April 1726 (buried 22nd Dec 1730), 19th Dec 1731 (buried 15th April 1765), 20th Oct 1736 and 5th March 1737/8. Other children of Thomas and Elizabeth Lewes, baptised at Fingringhoe are: Thomas (19th April 1724), Mary (Sep 1727) and Joseph (21st Sep 1735). Joseph, a farmer, possibly married Elizabeth Simons in Fingringhoe on 20th May 1762. The widow of Thomas junior is possibly the Elizabeth Lewes who married Joseph Laurence in Fingringhoe on 14th Sep 1763. |

| ↑4 | ERO ref: D/ABW 106/1/42. This will also mentions a granddaughter called Elizabeth Lewes – she may be the daughter of Thomas junior or Joseph – her parents aren’t mentioned in the document. |

| ↑5 | ERO ref: D/DU 251/88. Another item to look at on my next archival rummage…. |

| ↑6 | ERO ref: D/DU 251/94A. As above…. |

| ↑7 | Karl Marx, Das Kapital, Chapter 25: “The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation”. |