The starting point for tracing Hannah Southgate’s family were her marriages, the first in 1839 and the second in 1847. They both give her father’s name as James Angier. This led some to claim that Hannah and Mary May were sisters, but two local newspapers later refuted this. I was curious and decided to research what I could about their families to find out if they were related at all. If their father wasn’t the same man, then it was unlikely that the two women were even first cousins – it being unlikely that two sons would both be called James. [1]In all the research into my own family that I’ve done – thousands of people! – I’ve only ever found one parent who named two sons the same when the first was still … Continue reading

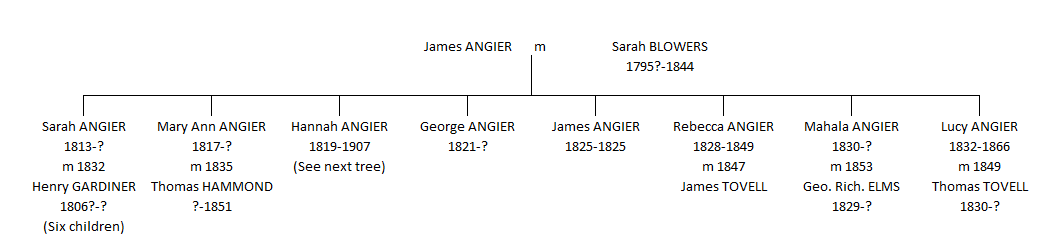

Having transcribed many records for Tendring, I looked in that village for Hannah’s baptism. I knew roughly when she was born, from the age given in the newspapers as well as the criminal registers, so I didn’t think she’d be too hard to find. There are five children baptised in Tendring with the surname Ainger, all with the father James, and mother Sarah between 1817 and 1832: Mary Ann (1817), James (1825), Rebecca (1828), Mahalah (1830), and Lucy (1832). But no Hannah. However, that gap between Mary Ann and James was perfect for Hannah, who would have been born in about 1819. Maybe they’d lived in a nearby village for a couple of years?

But then another thought struck me – I tried the non-conformist registers. And suddenly Hannah appeared, the daughter of James and Sarah Angier of Tendring, baptised on 6 June 1819 at the Methodist chapel in Manningtree, about 6 miles from their home village. The register even gave her date of birth – 7 May 1819. I also found another brother for Hannah, George, baptised at the same chapel on 1821.

I found a marriage for James and Sarah in Tendring, in October 1814. There is a three-year gap until their first child. But from the newspaper reports, it turned out there was another sibling for Hannah – her sister Sarah, who was married to Henry Gardiner, a butcher. They pop up when Thomas Ham is ill, and it’s Sarah who reports Ham’s death to the registrar. Before investigating the poisonings in the Tendring Hundred, local policeman Inspector Raison had helped Henry trace some meat that had been stolen from his cart! I couldn’t see a baptism for Sarah in Manningtree chapel or Tendring church, but I’ve found Sarah with Henry on the censuses from 1841 to 1871. It gives Sarah’s place of birth as Tendring, and a year of birth about 1813, so she might have been born just before or after her parents’ marriage. Henry was born in Great Bromley, and although I can’t find his baptism and so can’t trace him any further, the Gardiners in Great Bromley all seem to be related from a common ancestor called Henry, which means he’s very likely to be related to me via my grandma.

Having found that Hannah had a sister called Mary Ann, I wanted to check in case she became Mary May. But she couldn’t be. First of all, there was no link with the Constables – as we know, Mary May’s mother was called Constable, hence her half-brother was called William Constable. Hannah Southgate’s mother was Sarah Blowers when she married. Also, Mary Ann was too young to be Mary May – she’d married her first husband in 1825, when Hannah’s sister would have been about 8! Yes, I realise that baptism dates are not birth dates, but factoring in James and Sarah marrying in 1814, she still wouldn’t have been old enough to be married in 1825. To be on the safe side, I traced Mary Ann further. I found a possible marriage in Tendring in 1835, to Thomas Hammond, when she would’ve been 18. I found out that later, Thomas had committed suicide in 1851. I didn’t include this in Poison Panic as it was slightly outside the book, but I do wonder if he suffered from being the brother-in-law of “Lucky Hannah Southgate”. I think it’s extra evidence that Hannah Southgate and Mary May weren’t sisters. I did wonder if Hannah’s father could be Mary’s, if he’d been widowed before marrying Sarah, but he was a bachelor at marriage. Sometimes there are mistakes in registers, but it’s an outside possibility at most.

Sarah Blowers

I got slightly carried away tracing the family of Hannah’s mother. I found her on the 1841 census, aged 46, a poulterer, with daughters Rebecca, Mahala and Lucy. They had a servant called Mary Chisnal, who may have been like Hannah’s servant, Phoebe Reed, who helped run the house as well as pluck chickens for the business. It was interesting to see that Sarah had been a poulterer as it tied in with Hannah’s higgling business, which involved selling chickens. There was no James, but I’ve tried looking for his burial without any concrete success. When Mahala married in 1853, she said that her father was deceased.

I found a burial in Tendring for Sarah in 1844, aged 49. Using the Essex Wills Beneficiaries Index, I found Sarah – at least, someone called Sarah Angier – mentioned in the will of Rebecca Blowers. Rebecca lived in Weeley, and mentioned “my sister Sarah Angier.” I did some work tracing Rebecca, who was buried in Great Bentley, and mentioned several other close relatives in her will. It led me to, it seems, Hannah Southgate’s grandparents. Sarah was born in Great Bentley, the daughter of Nathaniel Blowers and his wife Sarah, née Demaid. This was very interesting, as Demaid is one of the Huguenot surnames in north-east Essex. There were eight Blowers children, including a Hannah, who may have given her name to Hannah Southgate. Nathaniel Blowers had left a will, and his headstone is in the churchyard at Great Bentley. His father, also called Nathaniel Blowers, had left a will too. They were the middling sort – a different family to the impoverished one that Mary May seems to have come from.

Hannah’s children

I could only find two children for Hannah by Thomas Ham. Thomas and Hannah had married on 11 December 1839 in Tendring, and Hannah was baptised in Tendring on 15 January 1840, although the family’s abode is Wix. Hannah had gone up the aisle pregnant, which wasn’t entirely unusual in those days (Sarah Chesham was probably pregnant as well when she married Richard). The child only lived two months, and was buried in Wix in March. Hannah may have felt trapped into marrying Thomas, hence her later animosity towards him, which might – or might not – have turned murderous.

The next child was Emily Lavinia, baptised in Wix on 8 August 1841, but I can’t find the baptisms of any further children. It was alleged during the inquest and trial, by Phoebe Reed, that Hannah had had several children who had died, but the only evidence I had was one, that first child who died aged two months old. Civil Registration of births, marriages and deaths had begun in 1837, so although I couldn’t find any further baptisms, surely there were births registered for all these children? However, searching for the surname “Ham” in the Tendring registration district, yields very few people. First of all, there are no births registered for Hannah or Emily Lavinia, no children registered just as Female Ham, either. There is an Anna Ham’s death registered in the March quarter of 1840, which could be that first child, and six others (Thomas was registered twice – the first in the June quarter of 1847 at his death, and then again in September 1848 after the inquest. One of Hannah’s descendants via Emily Lavinia sent off for both certificates, but was only allowed to see the first! Mysterious).

Not registering people seems rather suspicious, but flaky responses to the registration of life events wasn’t unusual, particularly with births. There are numerous anecdotal stories which pop up on genealogical forums where people remember their parent or grandparent not having a birth certificate and so having difficulty applying for their pension – and this went on into the early 20th century. The lack of baptisms for the children isn’t surprising either, as at the inquest, Phoebe Reed said that she and her mistress didn’t really bother with church or chapel.

So who were those children? When were they born? What were they called? We will probably never know. Does it mean she killed them all? Possibly not. The fact that there are no Ham babies buried in the Tendring Hundred between 1840 and 1848 except for Hannah, who is already accounted for, might suggest that Phoebe had fabricated the children. Because where on earth were the children buried? The back garden? If that hadn’t made the Coroner suspicious, or arch dog-collared busybody Reverend Wilkins prick up his ears, then I don’t know what would.

I could find no children of Hannah and John Southgate. It’s possible John had been infertile anyway, but it’s possible that an unchecked STD had caused infertility.

Speaking of Hannah’s husbands, their family trees proved quite interesting, too. Would you like to know more? Of course you would…. Thomas Ham and John Southgate.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | In all the research into my own family that I’ve done – thousands of people! – I’ve only ever found one parent who named two sons the same when the first was still living. This was Thomas Sallows, who named his first son Thomas. He remarried, after his first son had got married, and had children with his second wife (he was 51 and she was 24), they had a son and called him… Thomas! Fortunately Thomas pere left a will where he mentioned both of his sons called Thomas, but it was still mind-boggling. You can read about him on my page about Mary Cardinall and John Mash – you’ll probably notice that Thomas’s second wife was called Sarah Angier, and no, I’m not sure if she’s related to Mary May or Hannah Southgate! |

|---|