- Home

- /

- History

- /

- The Knightley family

- /

- Uncle Matthew’s letter and...

- /

- The Knightleys in Matthew’s...

Uncle Matthew’s letter to Robert Coke, written in 1557, reveals the names of many of his relatives (see transcription). One of the most important elements of the letter is that it tells us the name of William and Matthew’s father, and identifies their maternal grandfather. There are also dates which are useful for further firming up identities.

The Knightley pedigree given at the 1558 Herald’s Visitation of Essex states that Matthew’s parents were Thomas Knightley of Bent, Staffordshire, and a daughter of a Gifford. Bent in Staffordshire doesn’t appear to exist and is presumably an error for Brewood (pronounced “Brood”), where Matthew claims he was born, and also where the Giffords lived (and still do). The pedigree then gives John Knightley and Margaret, daughter of Thomas Daniell, as Thomas Knightley’s parents. The enormous Knightley pedigree in Miscellanea Genealogica et Heraldica (MGEH) gives Matthew’s parents as John Knightley and Mary, sister of “Thomas Daniell, militis” – Sir Thomas Daniell.

However, in his letter, Matthew states that his father was John Knightley, and his mother (he doesn’t give her forename) was the daughter of Thomas Daniell. The 1558 pedigree has erroneously introduced a generation between Matthew and his actual parents, making John Knightley and Margaret Daniell Matthew’s grandparents.

I will discuss the Daniells separately, but for now let’s look at what the letter tells us about where Matthew’s father fitted into the Knightley family, with some help from the pedigree in MGEH (which is quite muddled in some places, but helpful in others), Barron’s Northamptonshire Families (from the Victoria County History series) and what’s known about the Giffords.

- Knightleys in Staffordshire

- Knightleys in Northamptonshire

- The de Veres

- The Giffords of Chillington

- Charlton alias Knightley

- “A good poore man”

Knightleys in Staffordshire

Matthew mentions his uncle Robert Knightley of “Ingletone in Brude parish”, whose daughter Isabella married Matthew Morton. Morton was Matthew’s godfather and evidently, Matthew was named after him. MEGH gives us Robert Knightley of Engleton in Brewood, Staffordshire, the elder of the two brothers, and shows Isabella marrying Matthew Morton: arms, argent a chevron gules between three square buckles sable, impaling Knightley. The Collections for a History of Staffordshire tell us that Matthew Morton was still alive in 1504, but had died by 1530. The Mortons appear in the Staffordshire visitation. Matthew and Isabella had three children: John, Thomas (married Margery Shepperd of Oakley, Staffs. He died in 1558), and James (married Jane Downe. He died before 1566). Presumably they were born in the late 1400s, with Isabella (who is the same generation as Matthew Knightley) being born in the mid-late 1400s.

John Knightley and his brother Robert are shown in MEGH to be the sons of William Knightley of Calais, who died in 1431 and was buried at the Austin Friars church in the City of London: many notables were buried in the friary’s precincts, including John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford, in 1462.[1]More about the Austin Friars can be found on Wikipedia: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austin_Friars,_London> John and Robert’s mother is named as Margaret, without a surname, who was born in “Henoltia” – perhaps Hainaut in Belgium, which borders the north of France near Calais. MEGH states that Margaret’s father gave her land near Calais. Obviously, if their father died in 1431, that John and Robert were born either that year or earlier. As Matthew was born in about 1477 (according to Alumni Cantabrigiensis, which tells us when he studied at the University of Cambridge), John was at least 46 when he was born. William was likely born in the 1470s, too, and Thomas before them in the 1470s or 1460s, so John was clearly an older father.

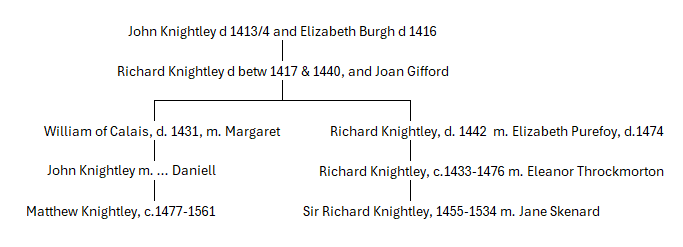

Matthew believed that his paternal grandfather had died at least a century before he wrote his letter in 1557, and William Knightley of Calais definitely had. So we have a match between Matthew’s letter and the MEGH, and it feels quite solid. Unfortunately, following the path in MEGH upwards from William, who died in 1431, we have a horrible muddle, where his parents are named as Richard Knightley and Ellena Cancellis, then his parents (William’s alleged grandparents) are named as Richard Knightley, 1433-1476, and Eleanor Throckmorton. It’s obviously impossible for someone to die before their grandparents are even born, so here the MEGH is very unreliable indeed. Other parts of Matthew’s letter, and more accurate parts of the MEGH can help, so we need to look at the extended family of Matthew’s father.

Knightleys in Northamptonshire

Matthew writes “Sir Richard Knightley of Faldsley 3 miles from Davitree in Northamtonshire said unto me that his grandfather & myne were brethen.” In other words, they were second cousins. Matthew is talking about his family who had moved to Fawsley in Northamptonshire, near Daventry. A daughter from this family married one of the Spencers, which means that, among many other people, Winston Churchill and William, Prince of Wlaes, are descended from the Knightleys. The specific Sir Richard that Matthew means was born in about 1455 and died in 1534. His son, Sir Valentine, was living at the time that Matthew was writing. He was born in about 1478 and died in 1566, so he was a contemporary of Matthew’s, even though Matthew (thanks to having an older father) was from the generation earlier.

This is where the Knightley tree gets confusing because there’s an unbroken line of several Richard Knightleys! Going backwards from Sir Richard, 1455-1534, we have his parents Richard of Fawsley, 1433-1476, and his wife Eleanor Throckmorton. Richard was the son of Richard Knightley and Elizabeth Purefoy. And finally we reach the couple who Matthew was descended from, along with the Knightleys of Fawsley – Richard Knightley, and Joan, daughter of John Gifford of Chillington.

The last-mentioned Richard was the son of John Knightley, and his wife Elizabeth Burgh. This is important, because the Knightley arms contain Burgh, along with Golovers and Cowley; according to MGEH, Elizabeth Burgh’s father, Adam Burgh, was the son of William Burgh and Eleanor Cowley. So that explains those elements of the coat of arms. MGEH then claims that Golover enters the fray when a William Knightley, who lived in the 1300s, married Dorothy Golover.

There is a tomb in the church at Gnosall, Staffordshire, with an effigy of a knight. Experts have dated the style of the tomb to the early 1400s, which would make it John’s resting place and memorial.[2]Note that for many years, it had been identified as the tomb of a man from another family, who had died in the 1300s.

This chart should help to set out what this all means thus far:

It was William of Calais’ brother, Richard, who bought Fawsley in Northamptonshire on 8 Feb 1414/5. Richard was clearly the older brother, as he inherited the properties in Gnosall, leaving William, as a younger son, to try to make his fortune elsewhere. The brothers must have been born in the late 1300s.

The de Veres

Matthew also mentions “My Lady Knightley, my Lord of Oxford’s daughter, sometime wife of Sir Edmund Knightley.” This is Ursula, who was a daughter of Sir George de Vere, who, contrary to what Matthew says, was never actually an Earl of Oxford. However, Ursula’s only brother, John, inherited the title and became the 14th Earl of Oxford. He was a wastrel, who died aged 26 in 1526. He had no issue, and without another brother to take the title, it passed to John’s second cousin, John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford (c.1482-1540). Matthew’s relationship to Ursula is perhaps significant: John Daniell, Matthew’s uncle, “was of the old Earles of Oxenfords councell and one of his executors.”

The Giffords of Chillington

As we can see from the pedigree above, Matthew was descended from the Giffords, and from the letter, we can see that he mentions “Dame Cassandre Jefforde”, his father’s first cousin (Matthew seems very certain of this, stating they were “full cosine jermines” – full cousins germaine). This would mean that John and Cassandra shared the same Knightley grandfather and grandmother. Looking at the pedigree, Cassandra would be a grandchild of Richard Knightley and Joan Gifford. Being the granddaughter of a Gifford perhaps explains why Cassandra married into the Giffords, as marriage of extended family, when wealth was at stake, was very common during this period. But how exactly does she fit?

Matthew states that Cassandra’s son Sir John Gifford was 98 years old when he died the year before, just before Christmas. This matches up exactly with Sir John Gifford of Chillington, who died 13 Nov 1556. He was born in about 1458, the son of Robert Gifford and Cassandra Humphreston.

Sir John’s mother is known to be Cassandra, daughter of Thomas Humphreston, thanks to an alabaster gravestone in Brewood church. Unfortunately, it’s no longer there, but it said:[3]From Brewood: a resume historical and topographical, by James Hicks Smith, 1874. (archive.org)

Hic jacet Domina Cassandra, filia Thomae Humferston, armigeri et uxor Roberti Giffard armigeri, ac domini de Chillington, ac postea uxor Joannis Brodocke, armigeri, quae Cassandra obiit die mensis Januarii anno Dom 1537 eujus anima propitietur Deus.

Translated:

Here lies Dame Cassandra, daughter of Thomas Humferston, armiger, and wife of Robert Giffard, armiger of Chillington, and afterwards wife of John Brodocke, armiger, which Cassandra died January 1537. Her soul is with God (or thereabouts!).

Thomas’ wife is unknown, so it’s possible that Cassandra’s mother was a Knightley, a daughter of Richard Knightley and Joan Gifford. Cassandra gave birth to Sir John in about 1458, and she lived until 1537. Just as her son died when he was nearly 100 years old, it seems like Cassandra was nonogenerian too; she was presumably born in the late 1430s or early 1440s. She was much younger than her husband, Robert Gifford, who was born in about 1401.[4]George Wrottesley wrote in great detail about the Giffords in Collections for a History of Staffordshire (archive.org) in 1902 As Richard Knightley and Joan Gifford’s sons William and Richard would’ve been born in the late 1300s, their sister, who married Thomas Humphreston, must’ve been born around the same time, and was presumably a younger sister. We don’t know how many other children the Humphrestons had: Cassandra may have been the younger of a large brood, hence she was born when her mother was likely in her 30s.

Matthew’s will names one of Cassandra’s descendants, his “Cousin Mistress Dorothy Shurleye” – I will write more about her.

Meanwhile, the MEGH gives us a Cassandra Knightley, who married first John Langtree, armiger, and secondly, John Gifford of Chillington, Staffordshire. There is no mention of a marriage to Thomas Humphreston. It also gives us Sir Richard Knightley, 1455-1534, as her brother, and therefore her parents would have been Richard Knightley and Eleanor Throckmorton. This means that the Cassadra in MEGH can’t be the Cassandra who married Thomas Humphreston. Of course, it’s not impossible that Richard had as sister called Cassandra, who married a John Gifford.

What’s important to note is that Richard Knightley and Joan Gifford had at least three children: Richard, William and a daughter who married Thomas Humphreston. Unfortunately, MEGH only shows their son Richard, as does the Victoria County History volume which covers Northamptonshire families. Due to those omissions, I wonder if I’m correct in assigning Richard and Joan at least two extra children, but Matthew’s letter is telling us that they must have had more children than just their son, Richard. And in order for William Knightley’s daughters Lettice and Winifred to carry the Knightley arms featuring Burgh, Cowley and Golover, he must have been descended from the Richard Knightley who married Joan Gifford.

Charlton alias Knightley

Matthew also mentions:

my great unkle Knightley maried a gentle woman which was the heire of the Charltons in Shropshire. The which gentlewoman would not marye with him excepte he would be called after her name Charlton, And soe because of the great lande he was contente, by these meanes all the worshipfull men of the Charltons which be very manye be Knightleys in dede.

(Matthew Knightley’s letter)

This is William Knightley, who married Anne Charlton of Appleby, Staffordshire. She was one of at least three children born to Thomas Charlton, who died on 6 Oct 1387 [11 Richard II]. Two documents transcribed in Collections for a History of Staffordshire[5] Vol. 15, 1894, pp.103 and Coram Rege, Easter, 3, H IV (March or April 1402) Vol. 16, 1895, pp.35-37: archive.org help us to understand what happened.

When Thomas Charlton (or “Thomas de Cherlton”) died in 1387, he left three children: Thomas jnr (b abt 1382), Anne, and Eleanor [Elena or Ellen in some records], (b abt. 1387). They were all underage. Thomas jnr inherited several manors and other property from his father, but because he was underage, he was a ward, and his wardship, plus his marriage, was bought from the king by John de Harleston, clerk and two others. Then, on 15 Feb 1388/9 [12 R II], Harleston sold it to John de Knightley.

John de Knightley died not long afterwards, on 20 Nov 1391 [15 R II],[6]The date of death helps us to potentially identify who this John Knightley is. He had married a woman called Ellen, and by 1391-2, she was a widow. and custody of the lands and Thomas jnr’s marriage fell to John de Knightley jnr., who would hold the lands until Thomas jnr, or any of Thomas senr’s heirs, came of age. The documents tell us that when Thomas jnr died, aged 17, on 31 Jan 1398/9 [22 R II], the property descended to his sister Eleanor – then aged 12 – and his nephew Thomas Charlton alias Knightley, Anne’s son, was aged 4. And that means that Anne had died before 31 Jan 1398/9.

Just to skip back a bit: the document transcribed in vol 16 tells that, after inheriting the custody of the de Cherlton’s property and Thomas jnr’s marriage, Anne had married William Knightley “without his will or assent, and they had issue Thomas.” It wasn’t at all unusual for people who owned wardships and marriages to marry off the rich, young wards to their own children, but in this case, the marriage went ahead without any discussion at all. It seems to have been a love-match, where Anne Charlton and William Knightley met because Anne was living living in the Knightley household.

William and Anne’s son Thomas was born in 1394 or 1395, so presumably the couple married in 1393 or 1394, within a couple of years of John Knightley jnr taking on the custody of the Charltons and their property. Although the Charlton children’s names are listed Thomas, Anne, and Eleanor, Anne may have been older than Thomas because the boys were listed first in these sorts of cases because they would automatically inherit the manors. Otherwise, Anne would’ve been about 10 when she decided to marry William, which seems rather unlikely. Even so, she was clearly a young bride, under 14 when her father died in 1387. She was probably born in the late 1370s. Despite her death at a young age, her son Thomas Charlton alias Knightley went on to live into his 60s, passing away in 1430.

How does William Charlton alias Knightley fit into Matthew’s family? Some online trees say that William Knightley died in about 1403, aged 29, but without any sources. It would mean he was born in about 1375. If he was Matthew’s great-uncle, he would have been a brother of William, Richard, and Cassandra Humphreston’s mother. It’s not unusual to see children given the same name as an older sibling. In fact, the Gawdeys went one better: a Thomas Gawdey named no less than three of his sons Thomas (although one of them, quite sensibly, changed his name to Francis). And it’s likely that William, Richard and Cassandra’s mother were born in the 1470s-1490s. So it’s plausible that there was a second William. The other option is that he was from the generation before, so he was a brother of Richard Knightley who married Joan Gifford, but this would make him fairly old by the time he married Anne. Also, there’s no William mentioned in the list of Richard’s siblings in Northamptonshire Families (but that doesn’t necessarily rule it out, seeing as the same book doesn’t given Richard and Joan any children other than Richard of Fawsley, and we know they had more children than that. It’s not impossible, of course – and it would mean he was Matthew’s great-great-uncle, rather than great-uncle, as stated in his letter.

John Knightley senior, who originally bought the Charlton wardship, was likely the son of Roger Knightley and his wife Sybill. His wife was a widow by 1391-2, which ties in with the date from the documents. He didn’t have any children, so John Knightley junior can’t be his son. However, he had two nephews called John – one was the son of Roger and Sybill’s second son (and heir), Robert, and the other was the son of Roger and Sybill’s fourth son, Stephen. It seems most likely that John Knightley jnr was the son of Robert, given that the Knightley property would pass from Roger to John senior to Robert (who died between 1383 and 1395), then to John jnr (who has the tomb at Gnosall). This would mean that the William Knightley who married Anne Charlton without permission was possibly the son or grandson of John Knightley jnr.

“A good poore man”

After all these wealthy Knightleys with their exchanges and purchases of land, it’s sobering that Matthew’s letter ends – after thanking his niece’s husband for the pair of gloves he’s sent him – with a mention of a Knightley who hadn’t done so well:

There is a tailear a good poore mann in Southwerke which callthe him selfe Knightley. His mothers name was Ringley he saith he was my brother Sir Thomas Bastord.

Matthew Knightley’s letter

The 1558 Essex Visitation names Thomas Knightley as a brother of Matthew and William, but says nothing more other than him being “son and heir”. The MGEH gives more detail: that he “genuit filium nothum e copore Mrae Ringley e quo magna familia in francia.” In other words, that Thomas had illegitimate children by Mistress Ringley, and that his family went on in France. Of course, Matthew is telling us that one of these children was living in Southwark, Surrey, by 1557. I should add that it’s not entirely clear that the name is definitely Ringley. Capital R and K are very similar at this period, so it could be Kingley. However, comparing the first letter of the name in the letter with appearances of Richard and Knightley, it does look more like an R than a K.

Although Matthew doesn’t give the forename of this “good poore man” in his letter, it seems likely that he is the William Knightley who Matthew names in his will, just before he names his legitimately born nieces: “William Knyghtleye, if he be alive.”

Footnotes

| ↑1 | More about the Austin Friars can be found on Wikipedia: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austin_Friars,_London> |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Note that for many years, it had been identified as the tomb of a man from another family, who had died in the 1300s. |

| ↑3 | From Brewood: a resume historical and topographical, by James Hicks Smith, 1874. (archive.org |

| ↑4 | George Wrottesley wrote in great detail about the Giffords in Collections for a History of Staffordshire (archive.org) in 1902 |

| ↑5 | Vol. 15, 1894, pp.103 and Coram Rege, Easter, 3, H IV (March or April 1402) Vol. 16, 1895, pp.35-37: archive.org |

| ↑6 | The date of death helps us to potentially identify who this John Knightley is. He had married a woman called Ellen, and by 1391-2, she was a widow. |