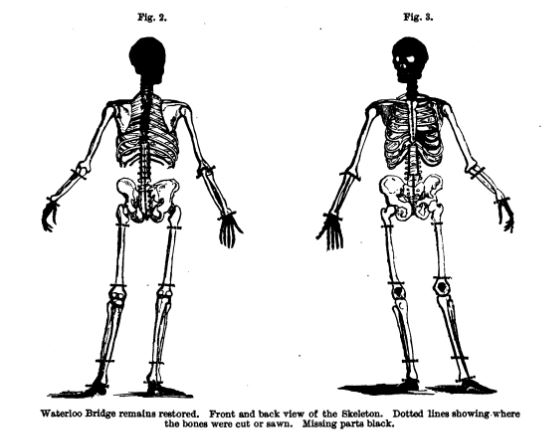

Have you heard “The Reclusive Skeleton of Fingringhoe” episode of Punt PI? In this Radio 4 series, comedian Steve Punt puzzles his way around cases of high strangeness, such as the Mull Air Mystery and The Crying Boy Paintings. It’s like Fortean Times on the radio. You’ll hear my dulcet tones chiming in, to talk about some of the research I did into the mystery of the skeleton. When a skeleton turns up, as they sometimes do – the image at the top of the page is from the 1857 Waterloo Bridge Mystery[1]It wasn’t strictly a skeleton as there was some flesh accompanying the bones – although not very much. – they exert fascination. How can we identify a person just from bones? Without the flesh, can we find out how they died?

The skeleton in the Fingringhoe case was found in 1949, in the apparently abandoned cottage of an actress called Ada Constance Kent, who hadn’t been seen since March 1939. She was reclusive and rather eccentric, so was the skeleton hers? But what about the children who had got inside her house and played there? I’ll leave you to listen to the programme, and if you’re interested in reading about what happened in the 1940s, then see the chapter in Patrick Denney’s Foul Deeds & Suspicious Deaths in Colchester (Patrick pops up on the radio programme too!).

I looked into Ada’s family background, tracing her in the censuses. I went off-piste a little and traced her mother, aunt and grandmother. These bits weren’t used on the programme, but it helped me to see Ada in context, as an ordinary girl from a riverside village in north-east Essex, who apparently came to an extraordinary end.

Start at the end

Working backwards from the information in the newspaper reports of the inquest when the skeleton was found in 1949, I found an entry in the death index for an Ada Constance Kent, as well as a burial in Coggeshall. I thought it odd that she hadn’t been buried in Fingringhoe, but supposed she had familial connections with Coggeshall, so wasn’t entirely reclusive. Coggeshall’s vicar had carefully entered dates of death beside everyone in the burial register, but none is given for Ada – it just says “Reported 22 March 1949”, and the age “about 77”. The address was The Cottage, Whalebone Corner, Fingringhoe, which matched up with the inquest reports, and I knew the cottage was opposite the Whalebone Pub (when I lived in Wivenhoe as a child, we used to go on New Year’s Day “row-and-ramble” outings – we rowed across the river from Wivenhoe, then walked to the Whalebone for a drink. At least, I sat on a swing in the pub garden with a lemonade and a bag of crisps).

I found a birth index entry for an Ada Constance Kent in 1871, which almost matched up with the “about 77” age in 1949. It was for the Lexden registration district, which I knew included Fingringhoe. I looked through my transcriptions for Fingringhoe but couldn’t find her baptism, nor could I find one in Wivenhoe, but she might not have been baptised at all, or could have been baptised in a non-conformist chapel whose records aren’t online yet. It’s worth sending off for birth certificates, but I decided to see what I could find on the censuses.

Censuses

There are no Ada Constance Kents on the 1881 or 1891 censuses born in Essex around 1871. But there is a Constance Kent, aged 9 in 1881, born in Fingringhoe, living on Shrubland Road in Colchester. She lived with her grandmother, Mary Ann Kent, a widow aged 58, and Mary Ann’s daughter – Ada’s mother? – 34-year-old Helen Ann Kent, a ‘tailor machinist’. Mary Ann had been born in Fingringhoe, and Helen had been born in Wivenhoe. Quite why you would willingly call yourself “Constance Kent” after the murder at Road Hill House, I can’t imagine, but there we are.

Rolling ahead to 1891, the same three women are at the same address (although Helen has become ‘Ellen’, which appears to be an enumerator error). But tracing Ada, or Constance, any further on the censuses proved impossible. I tried various variations of her name, I tried her stage name, ‘Vera Vershayle’, without luck. She vanishes, not on the 1901 or 1911 censuses. Even if I searched just by place and year of birth (Fingringhoe being rather small, this only throws up five women on the 1901 census), none checked out as her in disguise.

She could have gone abroad, but trying the same name-gyrations with travel and emigration records didn’t appear to yield her up. I wondered then if she had remained in the country but was a Suffragette, and so had scuppered the 1911 census by refusing to submit a return. “If you don’t trust me to vote, you don’t trust me to complete a census form.” And perhaps in 1901 she had been staying in a boarding house and, quite simply, her details were written down wrong.

I looked in the Fingringhoe electorial register for 1929 and she’s not there.

I looked for her on the 1939 Register and couldn’t find her on there either – and that does suggest to me that she wasn’t alive by September 1939. You couldn’t get a ration book unless you were on the Register, so perhaps she had died not long after she was last seen in March that year.

I was curious about her being buried in Coggeshall. I couldn’t do much about researching her friends, but might the answer lie with her family? So I went back to 1871, and the census that was taken just before Ada was born.

Helen Kent

On the 1861 and 1871 censuses, Helen Kent, her mother and sister Agnes were living in Church Green, Fingringhoe (the 1861 census unhelpfully misspells their surname “Kemp”). Mary Ann was a ‘tayloress’ in 1861. I went back another step to 1851, and found the family in Wivenhoe, on the High Street. Mary Ann was a 26-year-old widow; Helen was 3 and Agnes was only 1. They had a servant called Eliza Goodwin. Helen had been baptised in Fingringhoe on 19 September 1847 as Helen Ann Jennings Kent, the daughter of Joseph and Mary Ann. Her father was a mariner, and their abode was given as Wivenhoe. Agnes was baptised in Wivenhoe on 27 November 1849. A year later, on 4 November 1850, Joseph was buried in the churchyard at Wivenhoe; he was 30.[2]If you’ve heard the programme, then you’ll know the theme tune to Miss Marple runs though it, because Joan Hickson lived in Wivenhoe while playing the role of the sharp-eyed old lady. … Continue reading

I went back a step and found the marriage for Joseph and Mary Ann in Fingringhoe on 13 May 1847, which suggests that Mary Ann was pregnant at the wedding. It told me that Joseph was a Wivenhoe boy, the son of John Kent, mariner, and Mary Ann was the daughter of Thomas Pierce, shoemaker. The witnesses were Thomas Jennings (which might explain Helen’s middle name) and Joseph Fookes. They all signed the register except the bride.

I wondered if tracing Helen on later censuses would help me find Ada Constance. In 1898, Helen married a widower called Julius George Jarman. A rather fabulous name – was he in the theatre? No, he was a mechanical engineer. With such an unusual name, he was easy to find on the census, and there he was in 1901 on Military Road in Colchester. His son Percy from his previous marriage was living with him – he wasn’t in theatre either, but worked as a coach smith, and who should I find but Mary Ann Kent living with him? Aged 78, the redoubtable lady was ‘living on her own means.’ But I cannot see Helen Jarman, or Ellen Jarman on the 1901 census – it might be a clue as to where we might find her daughter.

On the 1911 census, Julius and Helen were in their sixties and living on Mersea Road in Colchester, Helen’s name given as ‘Hellen Ann Jenkins Kent Jarman’. The 1911 census is the first one where we see the household forms filled out by people themselves before being handed to the enumerator – Helen’s middle name ‘Jennings’ had been misspelt by her husband! There is, as you might have noticed, no mention of Ada Constance.

And then I searched the Coggeshall burial register and found that Helen Ann Jarman, aged 72, was buried there in February 1921, Julius following in 1929. Their abode was Coggeshall, so they must have moved to the village from Colchester after 1911 – they appear in the 1918 electoral register (but Ada isn’t there with them in Coggeshall). It explains why ‘the Fingringhoe skeleton’ was buried in Coggeshall, rather than the village it had lain desiccating in for so long. Perhaps it was put in the family grave, so hopefully the skeleton really was that of Ada Constance, otherwise there was a rather odd cuckoo in the nest – but who had arranged the burial? If she was a recluse, just how reclusive was she? Ada Constance knew the landlord of the Whalebone, because she bought cigarettes from him. She had a friend in Colchester, and she would sometimes disappear for months at a time. She received money from somewhere, and according to one of the Fingringhoe locals interviewed on Punt PI, letters would come for her via a Mrs Wade (one of my relatives!) with a crest on it – which apparently meant money. But from whom?

Then again, she had family. Although Percy, her stepbrother from the 1901 census, appears to have died in 1923, Julius had other children. But Ada Constance also had a whole raft of cousins, thanks to her Aunt Agnes. She married a carpenter called William Bird in 1874, and had at least eight children. They didn’t have theatrical careers – for instance, one of Ada’s cousins was a nanny – but they may have intervened when the very strange discovery in Ada’s cottage was made. Presumably when the inquest papers are released, there will a document somewhere to say to whom the remains were signed over for burial.

Mary Ann Kent

And then there was Ada’s grandma. She died 1904; not leaving a will, there was no clue there for Ada’s whereabouts at the time. Having transcribed Fingringhoe’s parish registers, I decided to trace her back before her marriage, just to see if I could turn up anything interesting.

Based on Mary Ann’s age on the censuses, she was born in 1823 or 1825; her death in 1904 said she was 82, which gives a year of birth of 1822. At her marriage, she claimed to be the daughter of John Pierce, shoemaker, and she gave her maiden name as Pierce. But the only Mary Ann Pierce baptised in Fingringhoe between 1813 and 1859 was the illegitimate daughter of Ann Pierce and Thomas Jennings. Thomas and Ann, who clearly were a bit slack when it came to getting on with walking down the aisle, had two more children before their marriage, and then finally got hitched in 1829. Another daughter followed in 1833.

On the 1841 census, Thomas is 72, a shoemaker, his wife Ann is 40, and then there is Mary, a son called Thomas (another shoemaker) and a daughter called Deborah. Thomas died in 1850, but this suggests he was the Thomas Jennings who witnessed Mary Ann’s marriage to Joseph Kent, and it also explains why Helen was given Jennings as a middle name (even if Julius got it wrong!). Thomas was 80 when he died, which suggests he was the Thomas baptised in Fingringhoe in 1769, the son of another Thomas Jennings and his wife Elizabeth. In turn, that Thomas was probably the son of John and Mary Jennings, baptised in Fingringhoe in 1738 – two hundred years before Ada Constance Kent was last seen in the same village.

The mystery lingers on

For all that Ada Constance Kent’s family tree can’t tell us if the skeleton found in the cottage really was hers, it can tell us some things about her. She disappears off the radar for a few years, perhaps for political reasons or perhaps just due to shoddy penwork. She went into the theatre, whether acting or, as has been suggested, to work as a sempstress in wardrobe. I actually wonder if she was a kept woman, which might explain the expensive ornaments and paintings on the walls – perhaps she’s not to be found on the censuses because she was living under an assumed name? But then we come back to the tantalising idea that she was a suffragette, and we see that she was born into an entirely female house, and her mother had grown up in a similar environment, the fathers always absent – either cold in the grave, or an unknown figure.

After travelling about, Ada found her cottage in Fingringhoe, and for all that she might not have interacted much with the locals, who viewed her as an eccentric recluse, she was, in her bones if not in her heart, one of them. It was where she was born, it was where her grandmother had been born. It was where her roots can be traced back to almost until the paper records run out.

What a curiosity it is. And how curious I am about those inquest records opening to the public in a few years’ time….

Footnotes

| ↑1 | It wasn’t strictly a skeleton as there was some flesh accompanying the bones – although not very much. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | If you’ve heard the programme, then you’ll know the theme tune to Miss Marple runs though it, because Joan Hickson lived in Wivenhoe while playing the role of the sharp-eyed old lady. And, let’s face it, it sounds like the sort of mystery that Miss Marple would end up involved in. Small village, eccentric lady involved in the theatre, local ties, strange disappearance, oh heck a skeleton! Ironic, then, that Hickson’s old house is mere metres from the churchyard where Ada Constance Kent’s grandfather was buried. |