Today, I went for a wander around the churchyard at St. Peter’s in Harborne, a suburb to the west of Birmingham. No, not in Essex or Suffolk, but a wonderful old place to rummage about in nonetheless. The church has a 14th century tower, but people have probably worshipped there since Saxon times, or before – it is where St. Chad of Mercia (to whom Birmingham’s Pugin-designed Catholic cathedral is dedicated) preached. This corner of Harborne has a distinctly “village” vibe. The cricket club is just across the road, and an ancient lime tree avenue runs across the pitch, from the church to Harborne Park Road.

It’s a splendid churchyard, with stones dating back to the late 18th century with fairly legible inscriptions (which I’ll write about in later blogs). It is canopied by tall, ancient trees, so that it always seems to be in an M. R. James half-light, a liminal space where history is breathing at your shoulder.

There are several ways into the churchyard: we entered from the gate by the junction of St. Peter’s Road and Old Church Road. The graves here are from the early twentieth century, so might be an extension of the original churchyard.

We were met at once by an extraordinary memorial, which is right up by the churchyard wall, to 17-year old Freda Strawbridge, who died in 1936, “result of a motor accident”. I don’t know when this was erected, but I had always assumed that a headstone like this – well – is a bit early 21st century. Sociologists seem to attribute the fad for headstones with drawings of steam trains, aeroplanes, teddy bears and cars on them to our post-Princess Diana mindset (before 1997, I don’t remember the British leaving floral tributes at the site of fatal accidents, but nowadays, it’s a national past-time). So this stone really stuck out, and when I read the dates on it, I was actually amazed that it is so comparatively early. 1936, really?

So does anything explain this memorial? Was it erected in the 1930s or later? I’m not entirely sure how I could find out (short of looking for the name of the mason and checking their records, which seems a tad too nosy even for me…). It doesn’t look all that new, of course. It perhaps replaced an earlier, plainer stone (or perhaps a wooden memorial) to James Upton, her maternal grandfather.

There are several newspaper articles from 1936 which report the accident wherein poor Freda lost her life. From the Hull Daily Mail, 5th October 1936:

TRIPLE ROAD CRASH

Girl Pillion Rider Among VictimsThree people were killed and three people were injured and three others are in hospital following a collision last night between two motor-cycles and a car on the Wolverhampton road, Oldbury, Worcestershire.

The victims were both the drivers of the motor-cycles and a girl pillion-passenger. They were William John Wilkinson (19), of Gilbert-road, Smethwick, Staffs; Leslie Frank Allen (20), of Lightwood’s-road, Smethwick; and Freda May Strawbridge (19), of Grosvenor-road, Harborne.[1]Source: British Newspaper Archive, accessed via Find My Past. Unfortunately Birmingham newspapers for this period aren’t currently available for the BNA.

The accident was also reported by the Gloucestershire Echo, Dundee Evening Telegraph, Portsmouth Evening News, Nottingham Evening Post and Sunderland Daily Echo & Shipping Gazette. This spread of reporting I think shows how shocked people were at the time by what had happened, and I think this probably demonstrates one reason why Freda was given her unusual memorial – her death was well-known. It’s possible it was paid for by a subscription from locals. I assume that Leslie and possibly William are buried in the municipal cemetery on Thimblemill Road on the edge of Bearwood, although it is a huge site and without consulting the cemetery records, finding their graves would be rather difficult (unless they too have similarly unusual memorials!).

Immediately we can see that Freda’s age is wrong in the article as she was 17 (as we can see from the memorial, and because she appears in the BMD index, being born in 1919), but the article had been printed very soon after the accident happened (presumably news of it was wired across the country), which perhaps accounts for the error. Freda was the daughter of William Henry Strawbridge, and his wife Elizabeth Upton, who were married in 1902 at St. Peter’s. They had at least four children. As well as Freda, they had three sons: William Stanley born in 1902, Graham Upton born in 1908 and Frederick J. born in 1912. Perhaps the gap between Frederick and Freda’s births was a result of William being away during WW1? In 1911, William was a worker at Carter’s brewery, and the family lived on Hampton Court Road in Harborne.

The family weren’t strangers to road accidents: in 1935, the year before Freda died, the eldest Strawbridge was injured in a motorbike accident himself. From the Western Daily Press, 5th August 1935:

Two Birmingham people had a lucky escape from serious injury on Saturday when, it is stated, their motor-cycle combination overturned in avoiding a cyclist at Alveston.

William Strawbridge (32), of Grosvenor Road, Birmingham, received bruises to the face, arm and legs and Miss Betty Stokes (18), also of Birmingham, injured her feet.[2]Source: Ibid.

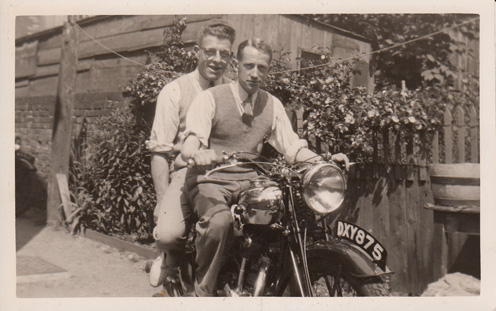

A ‘motor-cycle combination’ is presumably a motorbike and sidecar. In the 1930s, cars were beyond the means of most people, so motorbikes were more common. Below is a photograph of my grandad with his brother-in-law riding pillion, astride his A. J. S. (manufactured in Wolverhampton).

I assume this is sometime in the 1940s. During WW2, when he was a fireman and my grandma was sent away from Essex, up to Chester to live with her aunt (presumably Chester was thought to be safer than an east-coast village with a shipyard), he sent her a postcard where he mentioned that he managed to buy a packet of Woodbines (hurrah!) and that his motorbike fell over and it was so heavy, he had to wait for someone to come and help him lift it up. Grandad was hardly a “greaser” – motorbikes were just a way for people to get around. Once he was able to afford a car, my grandad bought one, and never rode on two wheels again. My other grandad, who trained up with the Canadians for their landing on Juno beach on D-Day, remembered the Canadian soldiers roaring up and down an airstrip, and, unsurprisingly, they didn’t go uninjured.

There is a photograph of Freda’s memorial on Flickr, taken in 2007. You can see that it has been cleaned since then (by family or by locals who are charmed by this unusual monument? I noticed that several stones have recently had a visitor scrape lichen away from the lettering on them). It’s interesting to note in the comments that someone has seen a similar one in the cemetery at Stretford, in Manchester – a wheel for someone who died in a motoring accident, from the same period. While people are scratching their heads, wondering why you would choose to memorialise someone with a representation of what killed them (perhaps a mean-looking Mycobacterium tuberculosis for those who died from TB?), I think it’s perhaps more to the point that the winged wheel commemorates the fact that Freda loved to ride.

Perhaps, simply, the Strawbridges were a family of petrol heads. They loved being out and about on their wheels, and so, when Freda didn’t come back from that last ride up the Wolverhampton Road, her memorial of the winged wheel was the most tenderly apt monument her family could think of. And that’s really rather sweet, I think.