After at last finding the connection between the Whittaker family and the Wade/Cardinall/Cooper/Tiffin families, I was feeling very pleased with myself.

But then another couple of wills came to light – those of James and Jane Kenerley of St Osyth, and even more links appeared.

James wrote his will in 1711, and it was proved on 20th May 1713 – this leads me to suspect his is the burial in St Osyth on 15th April 1713, “Mr James Kennarley”. Tracing his surname in the St Osyth register reads rather bleakly – it seems that none of his children survived. Both of his children baptised in St Osyth (Sarah in 1686 and Joseph in 1687) died in childhood, and a daughter called Sarah, who wasn’t baptised there, was buried in St Osyth in 1685. The children’s mother isn’t named in the baptisms, and I can’t see a possible burial for her, alas, but on 21 Feb 1690/1, James Kennerly and Jane Whitaker were married at St Mary’s-at-the-Walls in Colchester.

There’s no marital statuses in the register and no abodes, which isn’t particularly helpful. My hope is that a marriage licence allegation might turn up at ERO. But it’s not the end of the world, because James and Jane left detailed wills which show their connection to several families in Essex – and further afield in Cheshire, over 200 miles away.

A Cheshire connection seems bizarre, but on 11th October 1684 John Merry, “A Cheshireman” was buried in St Osyth. There’s also people from Cheshire in Beaumont-cum-Moze’s registers too: Thomas Darlington, Ottewell Doncastle (who died in St Osyth and was buried in Beaumont), Elizabeth Phthian and Robert Doncastle. In fact, surnames like Darlington and Doncastle suggest connections with still other places in the north of England.

James Kenerley’s will

In his will, James mentions his kinsman James Beeston of “Crue in Bartomley p’ish Cheshire”. I thought this was Crewe, everyone’s favourite railway station (“Change here at Crewe for trains to….”). Apparently Barthomley parish, in east Cheshire, was enormous – it contained five townships: Alsager, Balterley, Barthomley, Crewe and Haslington. But Crewe in Barthomley parish wasn’t Crewe with the railway station, so it was renamed “Crewe Green” to avoid confusion (of which there must have been a lot).

Then in the will there’s also Sarah Burging, sister of James Beeston. And Mary Loaton, wife of Edward Loaton of Allisger – I think it’s safe to assume this is Alsager. He doesn’t explain how he’s connected to these women, but then there’s kinswomen specified: Elizabeth Hamnet, Sarah Gallery, Sarah Stringer and Hannah Henbary and his cousin Mary Hollings. Then there’s “children of my cousin Sarah Stringer by her husband Dean” – presumably Stringer is husband #2 or more for Sarah.

Altogether, Kenerley’s legatees in Cheshire would receive £162 and 10 shillings (not including the 1 guinea to each of Sarah Stringer’s children – James doesn’t say how many children there are). Using The National Archives’ currency convertor, this comes out at about £12,500.

James then stated that William Whitacre, one of his executors, was to ride to Cheshire to dish out these legacies, for which effort, he would be paid £6 (about £450 now). I cannot think this is a task that William would have relished – the roads were full of highwaymen in 1713, and William would have been loaded with a very tasty amount of dosh. If you’ve read Lorna Doone, this might give you an indication of what William’s journey to the North and back was like. Did William make his journey in one piece? We may never know.

Aside from his kin in the North, James Kenerley also mentions people in Essex – all of whom appear to be connected to him via his wife, Jane. William Whitacre, his executor, is his son-in-law – a term which, at this time, could mean stepson just as much as it could mean “my daughter’s husband.” William receives £50 and his son James receives a guinea. There’s another son-in-law mentioned, John Whitacre. Then there’s lots of people who James doesn’t state his relationship to: Jane, wife of Abraham Clark; Randoll Whittacre (received £40 plus wearing apparel); George Grice of St Osyth, James and Isaac Grice; and, finally, James’ dairyman Thomas Robinson. And then there’s a landlady, Widow Web in Kelvedon – what was her connection to James and what did landlady mean in this context? There were Whitakers in Kelvedon at the same time – is there a connection here?

On reading this will it seemed fairly clear that the William Whitacre, his son-in-law who was sent on an epic and rather dangerous journey, was the William Whittaker who appears in St Osyth’s parish register from 1695, when he and his wife Sarah baptise their eight children there. John Whitacre, who is left lots of farming equipment by James, is probably the John Whittaker who had a wife Martha, and whose daughter Mary was baptised in St Osyth in 1722: John died in 1723 and in his will, he left everything to his wife. And I think that by son-in-law, James Kenerley meant what we’d know of as stepson. After all, his wife was called Jane Whittaker on her marriage, and of his two daughters, William named one Sarah (presumably after his wife) and one Jane – perhaps after his mother.

But seeing as Jane Kenerley, James’ widow, also left a will, would there be handy clues which would further explain how these people are related, and perhaps shine a light on the identities of those who appear in James’ will solely as a name?

Jane Kenerley’s will

Jane wrote her will on 23rd August 1717 and it was proved on 17th October that year: she was buried in St Osyth on 30th September.

Other than family members, who I’ll discuss below, Jane leaves money to her godson Ralph Shaw, and her friend Ann Phthian, widow. It’s likely that Ann Phthian moved in the same circles as Elizabeth Phithian, the “Cheshire woman” buried at Beaumont-cum-Moze in 1693.

In her will, Jane mentions three sons: John, Randall and William Whittaker. Presumably the “Randoll” Whitacre in James Kenerley’s will was the same Randoll, and therefore his stepson. There is a burial in St Osyth on 8th November 1733 for a Randall Whittaker. In fact, on 4th June 1704 a Randulph Whittaker “a stranger” was buried in St Osyth. Perhaps he was the brother of Jane’s previous husband? Then Jane mentions her granddaughter Jane, who was the daughter of her son William Whittaker – this would seem to be the child baptised in St Osyth in 1711, and who was buried there in 1729. Why this one granddaughter was singled out, I don’t know, but it seems likely it was because she had been named after Jane herself. As James Kenerley had only left a legacy to William Whittaker’s son James we might wonder if the child had been named after William’s stepfather (James Whittaker was baptised in 1708, nearly twenty years after James Kenerley had married Jane).

Three daughters of Jane then appear – Mary Theoball, Jane Norris and Elizabeth Cole. And then two more grandchildren – Thomas and Elizabeth Parsey, Elizabeth Cole’s children by her former husband, Parsey. This ties Elizabeth Cole to the Elizabeth Parsey in James Kenerley’s will, wife of Thomas Parsey – he was buried in St Osyth on 12th August 1712 as Mr. Thomas Parsey.

Jane appears to be the same Jane who is in James’ will as the wife of Abraham Clarke. I can’t yet see her marriage to Norris, but Abraham Clarke was buried in Great Clacton on 11 December 1713, and his will, written on 8th June that year, mentions his wife Jane, and Jane’s father Kennerley, who had left Abraham a legacy. Abraham’s will seems rather stingy to Jane – he left his property to kinsmen John Osborne and Richard Day, and Richard’s wife Susan. Jane was allowed to live in his large parlour on an annuity. It’s not surprising she decided to remarry quite quickly, although such a provision for a wife is by no means unusual. Abraham may have thought she’d marry again anyway and he didn’t want another man muscling in on his property, hence he gave it to his kinsmen who may have had a familial claim on it anyway if Abraham himself had inherited it from family.

I cannot find a marriage for Jane Clarke to Mr Norris, or Elizabeth Parsey to Mr Cole, but they are out there somewhere, and, conveniently with these two wills, we know Jane’s marriage had taken place between 1713 and 1717, and Elizabeth’s between 1712 and 1717.

But those two ladies aside, what about Mary Theoball? If the name seems familiar, this is no surprise – because you’ve seen that name before, rendered as a Theobald.

Whittaker/Theobald/Grice

On 14th August 1688, a marriage took place in Kirby-le-Soken between George Gris of Thorpe-le-Soken and Mary Whittacre of Kirby. Their children Mary, George and William were baptised in Thorpe-le-Soken between 1689 and 1694, and by 1697 the family were living in St Osyth, where five more sons were born – James, John, Joseph, Edward and Isaac. On 28th July 1711, George Grice, a yeoman, wrote his will: he mentions his wife, sons George, Edward, Isaac, James, Joseph and John, and a daughter called Elizabeth (I am yet to find her baptism). They were left variously property in St Osyth and Great Clacton, and the executors were James Kenerly and William Whitacres, both yeoman of St Osyth. Mr George Grice was buried in St Osyth on 30th August 1711.

A year later, on 14th September 1712, Mary Grice married Anthony Theobald in the church of St. James in Colchester. When Mary wrote her will on 5th February 1736/7, she was a widow: she mentioned her sons George Grice of Peldon, Joseph, Edward and Isaac, and two grandsons, John and Edward Vale – the sons of Benjamin Vale and Elizabeth his wife (Elizabeth had married Benjamin at St. Leonard’s, Colchester, on 29 Mar 1730/1). John and Edward Vale were to receive £20 each when they came of age, but if their father died before that time, the money would go to their mother Elizabeth, but with Anthony Theobald acting as guardian – this move was presumably required to prevent any later husbands of Elizabeth taking the money for himself. And two years after the death of Anthony’s wife Mary, he was to pay £140 to the executors.

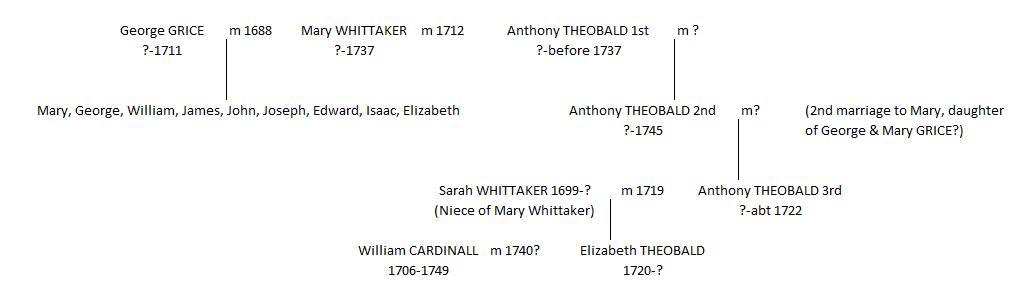

Going back to the 1721 will of Anthony Theobald jnr of Great Clacton, and the 1743 will of Anthony Theobald of St Osyth, the links between the Whittaker, Grice and Theobald families become clearer. There is a chain of three Anthony Theobalds – the eldest had married the widowed Mary Grice (née Whittaker) in 1712. He was already the father of Anthony Theobald 2nd. And in fact, Anthony Theobald 2nd’s son Anthony Theobald 3rd was already born. So…. seven years after Anthony 1st married Mary Grice, his grandson, Anthony 3rd married Sarah Whittaker in Great Clacton. But this marriage ended only two years later with the death of Anthony 3rd. At some point between 1712 and 1737, Anthony Theobald 1st died. And at some point before 1737, Anthony Theobald 2nd had married someone called Mary. Chances are, this was Mary Grice, the first child of George and Mary Grice (hence Mary Theobald directing money to be paid to the Grices after the death of Anthony’s wife), baptised in Thorpe-le-Soken in 1689 – but she would be too young to be the mother of Anthony 3rd. Then Anthony Theobald 2nd wrote his will in 1743. His wife had, presumably, died by this point, and he only mentions Martha Batterham, his granddaughter Elizabeth Carnel and her husband William Carnel (probably Cardinall) in his will. Erm… if you follow me!

As ever, a simplified tree will better explain this.

Mary Whittaker was the daughter of Jane Whittaker and her husband. Her brother William was the father of Sarah Whittaker. So that Mary was Sarah’s aunt, and Mary’s husband was the grandfather of Sarah’s husband. Or, to put it another way, Anthony Theobald 3rd married his stepgran’s niece. When George Grice nominated James Kenerly and William Whitacres as his executors, he was choosing his wife’s stepfather and her brother.

The wills help us to make sense of the parish register information, particularly as people move about a lot and, before 1754, don’t necessarily marry in the parish they were living in. Colchester seems to be a popular wedding venue, perhaps because it involved travelling to the nearest big town, so it was the fashionable place to get married if you had money to spare, as these families clearly did.

So we now can see that marriage between Anthony Theobald and Sarah Whittaker in a much clearer light, as well as fill out more detail about their families.

But as luck would have it, another will, that of Thomas Nunn of Great Oakley, might tell us something about Sarah Whittaker’s mother….