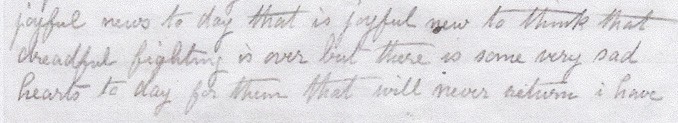

A guest blog for Findmypast. A letter written by my great-great-grandmother on Armistice Day in 1918 was full of clues for identifying my family. Would it unlock the mystery of my grandma’s Aunt Emily, and who was “poor Tom”?

A guest blog for Findmypast. A letter written by my great-great-grandmother on Armistice Day in 1918 was full of clues for identifying my family. Would it unlock the mystery of my grandma’s Aunt Emily, and who was “poor Tom”?

A guest blog for Findmypast. What happened to my grandma’s uncle, Ernest Baden Powell Field? And why did his marriages not quite match up with what I found on the 1939 Register?

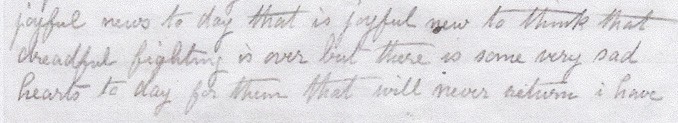

With the First World War 100th anniversary commemorations ongoing, I’m welcoming John Broom, author of Fight the Good Fight: Voice of Faith from the First World War to Essex & Suffolk Surnames. His book examines the way that faith and war combine – how one person’s faith might prompt them to seek after peace, whilst another’s inspires gung-ho nationalism. John looks at the experiences of people from many countries involved with the First World War, and uncovers previously untold stories of belief and bravery in the face of unparalleled destruction and despair.

His second book, about faith and the Second World War, will be out in April 2016.

So I asked him a few questions…..

A while ago I compiled all the unfortunate causes of death to be found in the parish registers for Beaumont-cum-Moze – perhaps the most unfortunate was William Taylor, who was killed by the bell falling out of the belfry. Burial registers aren’t really supposed to include cause of death, so they appear infrequently. But when they do, they give us a view into the lives lived (and the deaths died) in the past. Drowning and burning seems to have been more common than it is now, with people relying on well-water (and with all those rivers and creeks along the coast) and open fires. Of course, these are the deaths which have been described in the register – so they might be unusual, hence why they warrant a mention. And many causes of death not recorded may have been stranger still – it entirely depends on the whim of the minister or clerk entering the burials in the register. “Shall I mention that this poor chap was struck by lightning while harvesting turnips? Hmmm… nope.” It’s worth searching for your ancestors in newspaper databases in case they did have an unfortunate death which required an inquest.

Here’s some more, this time from Brightlingsea and Elmstead. The date is the burial date.

My Christmas guest blog for Find My Past. Arsenic at Christmas: a recipe for disaster.

Part two of my 1939 Register guest blog for Find My Past: An intrepid cocoa-buyer, and Uncle Bill’s fate.

Check out Find My Past for my guest blog about family tree brick walls I demolished with The 1939 Register. Without it, I would’ve struggled to trace Uncle Bill and Cousin Madge.

I’ve mentioned Grandma’s photo album before, when it turned out that the unnamed WW1 soldier posing in a Brighton studio was in fact her Uncle Bill. The photo above, of Grandma on a family seaside outing, interested me as it showed two of her cousins, and aunts of hers who I knew nothing about. She had written on the back identifying the people in the photo as:

I knew I would come across the burial of Matthew Hopkins, “witchfinder general”, when I came to transcribe Mistley‘s earliest parish register. It was still a strange feeling, to add his name to the database along with all the other residents. But along with Matthew, there was one other Hopkins in the register, and his burial seems to explain just what Hopkins was doing in Mistley in the first place, and perhaps how his campaign took hold.

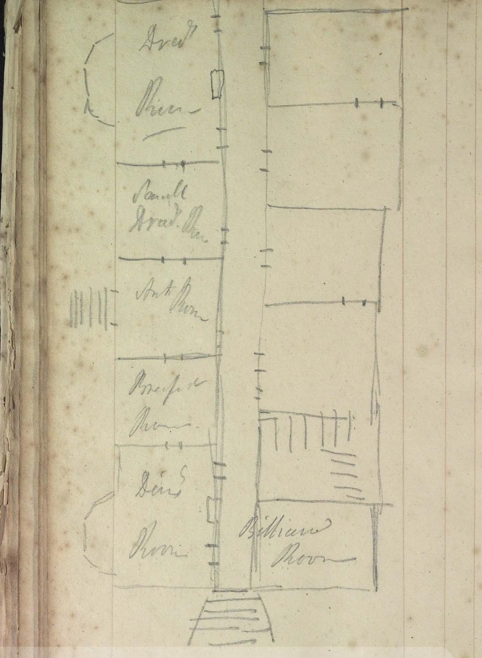

Well this is a very odd thing… a plan for the ground floor of a house, from Manningtree‘s register covering 1695-1775. It looks bizarrely like a board from the game “Cluedo”, not least because it even includes a billiard room. From the top, there’s the drawing room, something-or-other room, Ante? room, breakfast room and dining room. Some hastily added stairs, and bay windows.

But who sketched this? A vicar dreaming of his perfect house? Is there a house somewhere in Manningtree which was built to this plan?