Samuel, the last of Edward and Elizabeth‘s children, was born in Polstead, Suffolk, baptised there on 7th January 1779. The family moved back to Essex in the 1790s, and settled in Fingringhoe.

On 10th September 1801, he married Hannah Banks in East Donyland. Samuel was of Fingringhoe, and their first two children – Samuel William Cardinall Wade (1802-1848) and Shadrach Shakeshaft Wade (1804-1864) were born and baptised there. Betwen 1804 and 1807, the family moved to Wivenhoe, where Hannah Mehalah Wade was born on 18th April 1808.[1]Date of birth from her baptism, on 17th May 1808.

Hannah Banks

Hannah was born on 15th July 1783 in East Donyland, the daughter of Joseph Banks and Hannah (née Ruggles), and one of at least six children. Her parents married in East Donyland on 5th Oct 1773; her father was a widower from Wivenhoe, so that may explain why Samuel and Hannah later moved there – perhaps there were links with Hannah’s family.

Their children

Samuel and Hannah had eleven, possibly twelve children:

- Samuel William Cardinal (1802-1848)

- Shadrach Shakeshaft (1804-1864)

- Eliza (1806-1838) – possible child – see note below.

- Hannah Mahalah (1808-?)

- Matilda (1810-?)

- Alfred Thomas (1812-1859)

- Hermon (1814-?)

- Louisa Elizabeth (1815-?)

- Amelia (1819-1819)

- Cornelius (1820-?)

- Amelia (1824-?)

- Nathan (1827-28)

There are several memorial inscriptions for Wades in the Wivenhoe’s Old and New Cemeteries – many are descendants of Samuel and Hannah.

Notice that they only had one child carrying the Cardinal name – and it’s in the format “William Cardinal”, so if the other Wade researchers are correct, that Elizabeth Cardinal was the daughter of William Cardinal, then Samuel and Hannah’s first child was named after his father (Samuel) and his great-grandfather (William Cardinal) (or his late uncle, William Cardinall Wade).

Shadrach Shakeshaft’s name is harder to explain. Samuel’s sister, Sarah, had married John Lingwood, and we know John’s sister was married to Shadrach Seaman, which might be where the name came from, but the Shakeshaft name is unclear. There are other people who have the name “Shake” in their names in Wivenhoe (my 4 x great-grandmother, Hannah Maria Shake Spencer being of them), so it may be someone from Hannah’s father’s family. This will become clearer once I’ve transcribed Wivenhoe’s 18th century registers.

The name Hermon appears in another branch of the Wade family: Samuel’s sister Elizabeth Stone named her son, born in 1810, Hermon Whittaker Stone. Cornelius pops up again when Samuel’s nephew Charles Whittaker Wade (son of Edward and Sarah) names his son, born in 1834, Cornelius as well.

Eliza, the possible daughter

On the 1841 census, an 8 year old child called Georgiana Ross lives in the same household as Samuel, but without any explanation as to who she is (not surprising as the 1841 census didn’t include relationships). Another Ross appears with him on the 1851 census, a 19 year old niece called Eliza Ross, who had been born in Colchester. I investigated the Ross family, and found out that Eliza Ann Elizabeth Ross had been baptised at Colchester All Saints on 16th May 1830. Her parents were Andrew and Eliza Ross of St. Botolph’s parish, and her father was a tailor.[2]St. Botolph’s had long been in ruins – parishioners had to use All Saints instead. I found Andrew and Eliza’s marriage: 8th October 1827, again at All Saints. They were both of St. Botolph’s, and Eliza’s maiden name was Wade. The witnesses were Sarah Pratt, and then three Wades: James, Mehalah and Shadrach. I’m not sure who James is, but Mehalah and Shadrach are probably the children of Samuel and Hannah Wade, baptised in 1804 and 1808.

I continued – Andrew and Eliza had six children altogether. Eliza Ann Elizabeth, Georgina Louisa and Samuel Andrew were all baptised in Colchester between 1830 and 1834, but their last three children, Caroline Amelia, Mary and William, were baptised in Wivenhoe between 1836 and 1838.

William and Mary were twins, born on 10th March 1838, and Eliza was buried in the churchyad at Wivenhoe less than three weeks later, on 27th March. She was 32.

No other clues have appeared to suggest who Eliza’s parents are. I can only look at the three possible fathers and try to work it out from there.[3]All three of Edward and Elizabeth Wade’s daughters were married by 1806, so it’s unlikely she was an illegitimate child of theirs. William Cardinall Wade had died ten years before Eliza was probably born (about 1806), but there are still three other Wade men who could be her father: Thomas, Edward and Samuel were all married at this point. There doesn’t appear to be a gap in Thomas’ children where Eliza could slot in, so he seems an unlikely candidate. Edward seems more plausible – there is a gap where Eliza could fit (Leonora, possibly Edward and Sarah’s daughter, buried in 1803, then no other baptisms until Charlotte Lucretia was born in August 1807). But we also have to consider the rather loose way censuses were compiled sometimes, as well as terms like “aunt” and “cousin” not meaning what we expect: Samuel’s son Shadrach was baptised in 1804, and his daughter Hannah Mehalah was baptised in 1808 – Eliza, born about 1806, would fit in perfectly. And of course, Shadrach and Mehalah were witnesses of Eliza’s marriage to Andrew Ross – he repays the favour, witnessing Mehalah’s marriage in 1832.

Eliza on the 1851 census, Samuel’s “niece”, would, as the granddaughter of his brother, be his “grand-niece” anyway. However, it’s not beyond the bounds of possibility that she was in fact Samuel’s granddaugher, and “niece” was a mistake, or used as a catch-all. Sadly, I’m not quite sure how we can ever know for certain, beyond perhaps autosomal DNA testing of descendants. So Eliza will have to float, as a possible child of either Edward or Samuel. Samuel seems most plausible, though, considering two of Eliza’s children lived with Samuel at various points, and she moved to Wivenhoe from Colchester, where she died in 1838. Naming her first son “Samuel Andrew” might be very suggestive – the child being named after his grandfather as well as his father, maybe. Considering her husband was a tailor, as were two of Samuel’s sons, might also be a clue. Perhaps a baptism somewhere I haven’t thought to look yet will answer us… perhaps not.

Innkeeper, wheelwright, coal-dealer

Samuel’s occupation, which appears in the baptism entries for his children born post-1813, is an innkeeper and publican, but in 1820, a baptism says he was a wheelwright. It’s possible he turned his hand to both things. The 1841 census says he was a coal dealer, and this multiplicity of professions isn’t unusual – sometimes you see innkeepers who are also bakers.

An auction advert in the Ipswich Journal on 4th July 1807 mentions that “Household furniture, 2 useful Horses, 9 strong Shoats, Sow and 9 pigs” had been “Removed for Convenience of Sale, to Mr. Samuel Wade’s, The Falcon Inn.” Unfortunately there isn’t a note to say who all these things belonged to – either the estate of someone who had died, or that of a bankrupt. The auction wasn’t until 9th July – one wonders what Samuel and his family did with all of the auction goods, though The Falcon is well-known for being a large premises. It had to be, because the auction consisted of a huge amount of things:

Comprising 7 4-post and 2-post Bedsteads, various hangings, mahogany and other chairs, wainscot dining tables,[4]Appears to imply there was decorative carving along the table’s edge. a bureau bedstead,[5]No-one is quite sure what this means – British History Online has a couple of suggestions. 19th century US patents for ‘bureau beds’ appear to be for folding beds that resemble a … Continue reading Scotch carpet, painted buffet, 2 large canvas safes,[6]Possibly a kind of meat-safe. an alarum clock, an 8-day dial,[7]A clock that only needed to be wound once every eight days. large malt mill,[8]A machine used for milling grain for the production of beer. In many houses, this was a standard piece of kitchen equipment as beer was an essential element of the British diet. smoake jack, kitchen coal range, wind-up jack,[9]Roasting meat was done using jacks. A wind-up jack would presumably turn by itself, without someone having to sit in front of the fire and turn it by hand for the whole duration of the cooking time. … Continue reading patent oven, 3 standing stoves, lot of books, stone garden roll, boilers, saucepans, and kitchen utensils, 2 useful horses for road or harness, 9 strong shoats,[10]A shoat is a young pig. sow and 9 pigs, a loading cart, a light waggon, shafts, wheels, and springs of a chaise, and a variety of other articles….

Aside from this being an interesting snapshot of life for an innkeeper at this period, when all manner of activities took place down the pub, besides drinking and socialising (inquests, auctions, etc.), it also helps us to gain a more accurate idea of when Samuel and Hannah moved to Wivenhoe. It’s possible that he was a wheelwright whilst in Fingringhoe, then took the opportunity to change his trade and move to Wivenhoe to take over The Falcon.

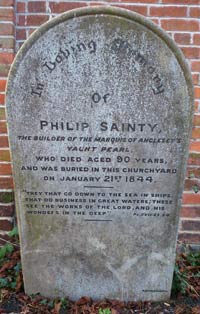

An aside about The Falcon: when I was a child, living in Wivenhoe, there were rumours about smugglers’ tunnels running under the Georgian part of town – the “old village” around the church and along the river. The Black Buoy pub claims to still have smugglers’ tunnels in the basement. The Falcon was supposed to have been a hot-bed for smugglers. Now consider that two of Samuel’s children married members of the Sainty family, and Philip Sainty, whose stone still stands in the churchyard of St. Mary’s, right next to The Falcon, was a convicted smuggler (not to mention, suspected bigamist!). The story goes that the Marquis of Anglesey arranged for Sainty’s release from prison so that he could build him a yacht, “Pearl”. Dare we wonder if Samuel had anything to do with the smugglers, or have I read Jamaica Inn once too often?

Although Samuel didn’t get in trouble for smuggling, he did get in trouble for violating his publicans’ licence. In 1831, Samuel C. Wade of Wivenhoe appears in the Essex Standard, having been hauled before the Petty Session at Colchester Castle along with other WIvenhoe publicans. “Sharp work among the beer shops”, says the report.

We last week noticed that summonses had been issued against William Sherman, Samuel C. Wade, Isaac Ladbrooke and William Baxter, keepers of beer shops, in the parish of Wivenhoe, to answer the information preferred, charging them with offending against the terms of their respective licences.[11]Essex Standard, 31st December 1831.

The offenses committed were to sell beer outside of the times stated under licensing law. Samuel was charged 40 shillings per offence, resulting in a fine of £8, which is a considerable amount. Note that his name is given as Samuel C. Wade: I did wonder if this was in fact his son, Samuel William Cardinall Wade, but Samuel jnr is always a mariner when he appears in registers and in his will, so it seems most likely that this was Samuel snr. If this is so, then it might suggest that Samuel senior’s middle name was Cardinal, just as his brother William‘s had been. However, this is the only instance I have yet seen of Samuel senior’s name appearing like this.

In 1838, Samuel got caught again.[12]Essex Standard, 23rd February 1838. Accessed from the British Newspaper Archive via Find My Past. William Reeves, the constable, was sent to inspect the pubs on a Sunday by the bench, because

…several respectable inhabitants of Wivenhoe and [East] Donyland, having made repeated complaints to the Bench, that the publicans in these parishes (though repeatedly cautioned), made it an invariable practice to keep their houses open during divine service on Sundays.

Along with Samuel, who was now landlord of The Greyhound pub, were other Wivenhoe publicans: John Chamberlain of the Ship-at-Launch, William Abbott of the Flag and Edward Scofield of the Horse & Groom, and two East Donyland men: Thomas Mortimer of the White Lion (which Samuel’s son-in-law ran for a time in 1835 – see below) and Robert Pitt of the Ship.[13]Three of the pubs involved are still open to this day – the Greyhound, Flag and Horse & Groom.

Samuel was found to have had “four persons in the tap-room, drinking, at a quarter before twelve o’clock. They were all sailors and lived in the place.” The front door wasn’t fastened so although Reeves didn’t see anyone actually buy any alcohol, the fact the door was open was enough to make Samuel appear rather guilty. He stood his ground, protesting that:

…he let two persons into his house after they had been to chapel, but no beer was drawn them. He wished to know whether he was not allowed to admit persons who attended a dissenting chapel into his house after their service, although divine service at Church was not over, instead compelling them “to stand in the cold and be perished.”

Samuel was told “he must know that he was not allowed to open his house except for the reception of travellers at that time.” It’s an interesting observation for Samuel to have made, because it points out how Anglican-centric England was at the time: the Established Church was all. The concept of divine service, for the purposes of licensing law, was defined by the time of the service at the Anglican church, St. Mary’s – the two people Samuel admitted, who he claimed had been to the dissenting chapel, had probably come from the Congregational.[14]I rather like the image of Dissenters heading down the pub immediately after chapel! It does seem rather unlikely, but a lot of village business was carried out in pubs. But the rest of the article makes it plain that the law was in some respects unenforceable, because the time of divine service varied from parish to parish. What’s interesting too is that the report carries speech which Samuel apparently said – it’s fascinating all these years later to actually “hear” him. Nevertheless, he was charged 10 shillings and made to pay another 11 shillings in costs – not wonderful, but an improvement on the far larger fine he was made to pay seven years earlier.

In 1835, Samuel helped his son-in-law William Sainty, who had married Louisa Elizabeth the year before, to go into business as a publican in East Donyland. We can see William and Louisa’s marriage in Wivenhoe on 27th August 1834, and their first child, Cardinal Nathan Sainty, was born rather soon after in the November of that year.[15]Cardinal Nathan Sainty became a master mariner and emigrated to New Zealand. Their next child, Louisa Selina, was born on 31st October 1835, baptised in Wivenhoe on 17th January 1836, but their abode being given as East Donyland.[16]She died an infant, not long after her baptism, and was buried in Wivenhoe. The baptism of their daughter Henrietta in January 1837 shows they had moved back to Wivenhoe. At the baptisms of both Cardinal and Louisa, their father’s occupation is given as a shipwright, but a report from the magistrate’s court in 1841, over an apparently unpaid promissory note from 1835, says that in 1835, William Sainty “took the White Lion at East Donyland, of the plaintiff, and gave the note in hand […] in payment of the fixtures. He remained in the house seven months.”[17]Chelmsford Chronicle, 23rd July 1841. Note that the White Lion was one of the pubs involved in the sting operation to crack down on inns serving beer during divine service. William’s foray into innkeepership didn’t last very long, clearly. They ended up having to go to the magistrates at Colchester Castle because Mr. Garrad, who lent them the money, claimed that it had never been paid, but both Samuel and William protested that it had been – the jury found in Samuel and William’s favour.

In 1844, Samuel’s business endeavours came off the rails – he was declared bankrupt. He was both innkeeper and coal-merchant, but clearly trying his hand at both did not pay off. According to the London Gazette,[18]14th May 1844 Samuel was in fact imprisoned at Chelmsford gaol: “Out of business, previously Publican and Dealer in Coals.” Unfortunately, bankruptcy was a very real risk for any businessman, and in the past, the bankrupt were put in prison until some way to pay off their debts was arranged. In some ways, it’s lucky Samuel’s bankruptcy happened towards the end of his life, when he no longer had a young family to support, and his wife had died in 1839, so he didn’t have her to worry about either.

What caused his bankruptcy isn’t entirely clear – if his business faltered, or if other factors came into play. A report in the Chelmsford Chronicle on 12th July 1844 may explain it. It seems to concern an estate in East Donyland, which was mortgaged in 1827. It was assigned to Dr. Barton, Dean of Bocking, for £500, and the detaining creditors became Barton’s executors. They applied to Samuel to sell the property, but he was unable to sell all of it because an elderly woman who “had resided in it some years […] made a sort of claim to remain there for life. The executors then felt bound to take all means for obtaining the money.” Samuel had perhaps already retired and didn’t have the financial resources to cope with their demands, so at 65, he ended up in prison, through no fault of his own. It would be interesting to find out what the estate was and who the old woman concerned was (she could well have been one of Samuel’s relatives). However, Samuel made it out of debtor’s prison and went back to his family in Wivenhoe.

Suffolk, Essex, County Durham

Hannah died in 1839, and Samuel apparently didn’t remarry. On the 1841 census, Samuel is a coal merchant, living on the High Street, near Blythe Yard. He had his son Shadrach, a tailor, living with him, as well as Shadrack’s wife Sarah and their daughters Sarah and Caroline. Samuel’s sons Alfred, a carpenter, and ‘Harman’, a tailor, also lived with him, as did Georgiana Ross, who is possibly Samuel’s granddaughter. A 24-year old woman called Sarah Cook also lived with them – I’m not quite sure how she fits in. No occupation is given, and her name comes under that of Georgiana’s – was she a border, or a servant, or an as-yet unidentified servant?

In 1851, back in Wivenhoe after his brief stay at Chelmsford gaol, Samuel was living again on the High Street, with his married daughter Amelia Wear, and his “niece” (possibly granddaughter) Eliza Ross. Amelia had married Jonathan Mitchell Wear from Scarborough a few months before – he was a mariner, so presumably Amelia lived with her father while her husband was at sea.

Another of Samuel’s daughters, Hannah Mahalah, had married a mariner from Scarborough, too, in 1832; Captain Robert Dodds of the brigg “Mary”. This connection with the north-east of England is pertinent – for a long time, I couldn’t find the record of Samuel’s death, looking in Essex, and peering through burial registers in villages along the River Colne. However, it was a report in a newspaper that finally solved this last mystery. I think Samuel must have gone to live with one of his daughters as an elderly man, and he died in the north. From his birth in Suffolk, to his family’s return to Essex, he ended his busy life in County Durham:

April 5th, at South Shields, much respected by a large circle of friends, Mr. Samuel Wade, formerly a merchant, of Wivenhoe, aged 74.[19]Essex Standard, 23rd April 1852.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Date of birth from her baptism, on 17th May 1808. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | St. Botolph’s had long been in ruins – parishioners had to use All Saints instead. |

| ↑3 | All three of Edward and Elizabeth Wade’s daughters were married by 1806, so it’s unlikely she was an illegitimate child of theirs. |

| ↑4 | Appears to imply there was decorative carving along the table’s edge. |

| ↑5 | No-one is quite sure what this means – British History Online has a couple of suggestions. 19th century US patents for ‘bureau beds’ appear to be for folding beds that resemble a chest of drawers when packed away. |

| ↑6 | Possibly a kind of meat-safe. |

| ↑7 | A clock that only needed to be wound once every eight days. |

| ↑8 | A machine used for milling grain for the production of beer. In many houses, this was a standard piece of kitchen equipment as beer was an essential element of the British diet. |

| ↑9 | Roasting meat was done using jacks. A wind-up jack would presumably turn by itself, without someone having to sit in front of the fire and turn it by hand for the whole duration of the cooking time. Before this innovation, small dogs were used in treadmills attached to the fireplace, and were specifically bred for the purpose – the “turnspit dog” or vernepator cur, short-legged and long-bodied. It is now extinct. |

| ↑10 | A shoat is a young pig. |

| ↑11 | Essex Standard, 31st December 1831. |

| ↑12 | Essex Standard, 23rd February 1838. Accessed from the British Newspaper Archive via Find My Past. |

| ↑13 | Three of the pubs involved are still open to this day – the Greyhound, Flag and Horse & Groom. |

| ↑14 | I rather like the image of Dissenters heading down the pub immediately after chapel! It does seem rather unlikely, but a lot of village business was carried out in pubs. |

| ↑15 | Cardinal Nathan Sainty became a master mariner and emigrated to New Zealand. |

| ↑16 | She died an infant, not long after her baptism, and was buried in Wivenhoe. |

| ↑17 | Chelmsford Chronicle, 23rd July 1841. Note that the White Lion was one of the pubs involved in the sting operation to crack down on inns serving beer during divine service. |

| ↑18 | 14th May 1844 |

| ↑19 | Essex Standard, 23rd April 1852. |