If you’ve ever read The Woman in White, then you’ll know that all the mystery and obfuscation, the swapping of people drugged on laudanum and signing of parchment documents, revolves about Sir Percival Glyde’s attempt to marry a wealthy woman to cover his debts, and to hide his illegitimacy. Had his mother not been married to another man, preventing his parents’ marriage, had divorce been easier to obtain, then there would have been no need for him to go to the great lengths he does to hide his secret, and neither would he die horribly in a conflagration in a church vestry. But without being a lawful (ie. legitimate) heir, and as his father did not leave a will, Sir Percival Glyde is a fraud. He could not have inherited his title and property from his father by default.

Far back in the past, before Marian Halcombe and Laura Fairlie decide it would be amazing to have an art tutor (especially a handsome one…), Percival manipulated Mrs. Catherick to help him gain access to the church vestry. And why would he want to do this? Because he wanted to fraudulently edit the marriage register.

Remembering the account which Marian had given me of Sir Percival’s father and mother, and of the suspiciously unsocial secluded life they had both led, I now asked myself whether it might not be possible that his mother had never been married at all. Here again the register might, by offering written evidence of the marriage, prove to me, at any rate, that this doubt had no foundation in truth. But where was the register to be found?

Central to the novel is the possible distance between a living person and the paper proofs of their identity. Without his parents’ marriage, Sir Percival Glyde is not who he claims to be; with Laura Fairlie alive, but another woman dead in place, she can no longer claim her name. As a genealogist, the novel is very interesting on this score. Collins, who trained as a lawyer, would have been well aware of the different ways people could prove their identity, and these are the same ones that we use when compiling our family tree.

Walter Hartright goes to the old church at Old Welmingham to look in the register, and is surprised by the lack of security – consider how many registers have been lost, stolen or damaged, and the conditions in which this register is kept in is perhaps typical of many churches in the past:

He opened the door of one of the presses—the press from the side of which the surplices were hanging—and produced a large volume bound in greasy brown leather. I was struck by the insecurity of the place in which the register was kept. The door of the press was warped and cracked with age, and the lock was of the smallest and commonest kind. I could have forced it easily with the walking-stick I carried in my hand.

Walter looks through the register, searching for a marriage happening around 1804. Anyone who has done the same, researching their family, can identify with Walter as he searches:

I began my backward search with the early part of the year. The register-book was of the old-fashioned kind, the entries being all made on blank pages in manuscript, and the divisions which separated them being indicated by ink lines drawn across the page at the close of each entry.

This is where understanding the history of parish registers is useful. I have seen three different kinds of register used to record marriages before 1813 – in that period following the changes wrought by Hardwicke’s 1753 Act, which came into force on 1st January 1754.

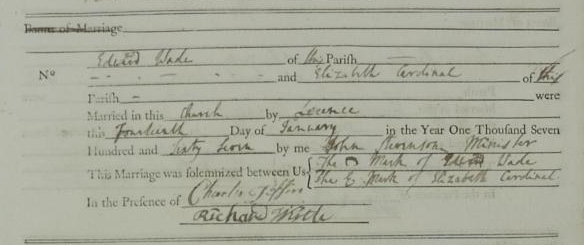

Firstly, there are the most formal registers of all, which I have seen most often. This shows the 1774 marriage of my 6 x great-grandparents, Edward Wade and Elizabeth Cardinal, at Layer-de-la-Haye:

You’ll see that places are given for the bride and grooms’ names to be entered, and the place to state which parish they’re from: either just “this” parish, or “the” parish “of Wherever”. Marriage by banns or licence can be indicated, then a space for the bride and groom to mark or sign (you’ll see here that although Elizabeth marks, her mark is in fact the letter E, which suggests she wasn’t illiterate). Below that, two lines for the witnesses to sign or mark. Had they married by banns, and had a separate banns register not been used, then the dates on which the banns were published would have been included at the top of the entry (although often these dates don’t appear). You can see, to the left of the groom’s name, “No.” – these registers did not have the numbers of each entry printed in them, it was up to the clergyman to add it himself. Post-1813 marriage, death and baptism registers all have these numbers printed in them – presumably because not having this in the register already made the registers vulnerable to fraud.

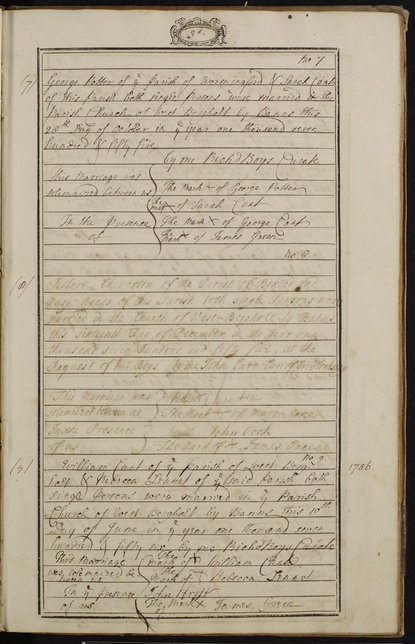

Each side of the page had space for four entries (be they marriages, or of banns for marriages performed at another parish). At the front of this register, it says “London: Printed for Thos. Lownds Bookseller near Exeter Exchange, MDCCLIV.” The bookseller’s name is written in by hand, so it seems that one printer had been given the contract to produce them, and then clergy approached a bookseller of their choice to buy the register. Over in West Bergholt, a different kind of pre-printed register was being used, a far less formal version:

It might have an elaborate graphic at the top of the page (which clergymen used variously for entering the year, or the page number), but it completely lacks any other kind of formal constraint, other than providing printed lines, so at least the handwriting wouldn’t be wonky. It allows for flexibility, but one wonders the wisdom of allowing flexibility when dealing with a legally-binding contract, such as a marriage. Considering Hardwicke’s Act was designed to formalise the process, these marriage registers seem to miss the point, but it was a legal register, and an improvement on what had gone before (sometimes nothing more than the date and the names of those being married). You can see how the entries are still trying to follow the new format – bride and groom are named, their parishes are included, and then they mark or sign, as do the witnesses, and each entry is numbered. However, because the space isn’t properly laid out, as in the more formal registers, you can see that there’s problems trying to legibly fit all the information in.

This particular register was printed and sold by J. Coles, stationer, of Fleet Street in London. Once it was full, by 1790, it was replaced by a new register, in the formal format.

But if the informal printed register seems open to fraud, then some parishes carried on using parchment or paper, not using printed registers at all. Wethersfield in Essex is one such place, and in fact, the Brontë’s father, Patrick, was curate there from 1806 to 1809.[1]It seems appropriate to mention Patrick – Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is seen as a precursor to Sensation Novels, of which The Woman in White is a famous example. You can see his handwriting in the last two marriages on this page, and if you look at the larger version of this image, you’ll see his signature too:

They at least used a ruled paper book. Before 1796 (when they started to use the formal register), Langenhoe continued to use its old parchment register:

However, they did at least use the proscribed format, and in some cases, the parchment registers have survived better than the paper ones. When the move came in 1813 for baptisms and burials to be recorded in printed paper registers as well as marriages, some parishes neatly drew out the boxed form which appeared in the printed version in their parchment register, saying that it was preferable than paper: they were, however, soon stopped on the bishop’s visitation….

What all these examples serve to show, then, is that Wilkie Collins had knowledge about old parish registers, probably through his time training in law. To return to Walter Hartright, he said “The register-book was of the old-fashioned kind, the entries being all made on blank pages in manuscript, and the divisions which separated them being indicated by ink lines drawn across the page at the close of each entry.” Presumably, then, this is a register like the one used in Langenhoe, although the 1982 television series uses the informal printed version, as used in West Bergholt. I have to say, watching this version, I was very impressed by their attention to detail, even down to the type of marriage register used!

In order to commit his fraud, Glyde was lucky that the formal printed register had not been used at Old Welmingham. Walter finds the marriage entry for Glyde’s parents (which it turns out Glyde entered himself in a space in the register):

It was at the bottom of a page, and was for want of room compressed into a smaller space than that occupied by the marriages above. […] . The entry immediately following it (on the top of the next page) was noticeable in another way from the large space it occupied, the record in this case registering the marriages of two brothers at the same time. The register of the marriage of Sir Felix Glyde was in no respect remarkable except for the narrowness of the space into which it was compressed at the bottom of the page. The information about his wife was the usual information given in such cases. She was described as “Cecilia Jane Elster, of Park-View Cottages, Knowlesbury, only daughter of the late Patrick Elster, Esq., formerly of Bath.”

The reason it has been squashed in is because Glyde has had to force it into a gap which, thanks to the format of the register, was available to him so he could perpetrate his fraud. You sometimes see, where a clergyman has accidentally missed a space in a register, that they go back and draw a line through it, noting “Omitted by mistake” – presumably to stop precisely the sort of fraud that Glyde carried out. Fortunately, a solicitor had kept constantly-updated, official copy of Old Welmingham’s register in his office. Walter pays a visit and finds “Nothing! Not a vestige of the entry which recorded the marriage of Sir Felix Glyde and Cecilia Jane Elster in the register of the church!” Glyde has been rumbled, and his firey death follows swiftly thereafter.

What’s rather interesting, bearing in mind so much of the plot revolves about this fraudulent marriage, is that Walter and Laura themselves seem to be involved in a marriage fraud.

Once Laura recovers (although she never recovers entirely), she, Walter and the ever-present Marian go to the seaside, ” a quiet town on the south coast”, where they are unknown and where Walter and Laura marry. At this point, Laura is officially dead – Ann Catherick, ‘the woman in white’ herself, died and Glyde had her death registered under Laura’s name (when you’ve performed one fraud, why not commit another?). So how can Laura marry as Laura Fairlie?

We may wonder the same thing when ancestors put things in marriage registers which are untrue. For instance, my great-great-grandmother, Elizabeth Shrimpton, was illegitimate, but on her marriage in 1859 gave the name “Joseph Shrimpton” as her father – this was actually her grandfather. These facts were not checked. It appears to be sufficient that, if you married by banns, no-one came forward in the allotted time with a reason why the marriage should not go ahead. Proving your identity was not required (although these days it is), maybe because living in a less bureaucratic age, with high levels of illiteracy, meant most people didn’t have ready access to paper ID, and perhaps the fact that the marriage happened in church was thought a deterrent to fraud – no-one would tell a fib in a church, would they? The witnesses to the marriage did not even have to know the people getting married.

Presumably Walter and Laura married by licence – they seem to marry rather quickly – so that if it turned out they had married illegally, Walter would have had to pay a fine. As it is, after the marriage, he forces Count Fosco to write a confession, which is then used to prove Laura’s identity, which is reinforced by her uncle (surely the most pathetic, annoying character in any novel ever written? A man who happily sacrifices his niece to a scoundrel just because stirring himself even slightly gives him a headache) publically acknowledging her.

Inevitably, I wonder if I had ever innocently transcribed a forged entry which someone had entered, Sir Percival Glyde-style, in a register….

Images reproduced by courtesy of the Essex Record Office.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | It seems appropriate to mention Patrick – Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is seen as a precursor to Sensation Novels, of which The Woman in White is a famous example. |

|---|