- Home

- /

- History

- /

- The Griffin family

- /

- William and Mary Griffin

- /

- Daniel Griffin (1757-1835), Sarah...

- /

- Thomas Griffin (1788-1860) and...

Thomas Griffin was baptised on 21 March 1788 at the parish church of Aston Clinton, Buckinghamshire, the first of nine children of Daniel Griffin and Sarah Fowler. His parents had been married barely three months earlier, in early December 1787.

In 1802, when he was fourteen, Thomas was apprenticed to a trade. Thomas was sent to Aylesbury, where he was the apprentice of Thomas Deverell. It’s interesting that, despite being the oldest son, he wasn’t going to follow in his father’s or even grandfather’s footsteps and become a yeoman or a farmer. But then, none of Daniel and Sarah’s children stayed in the area; all of them headed to London and beyond.

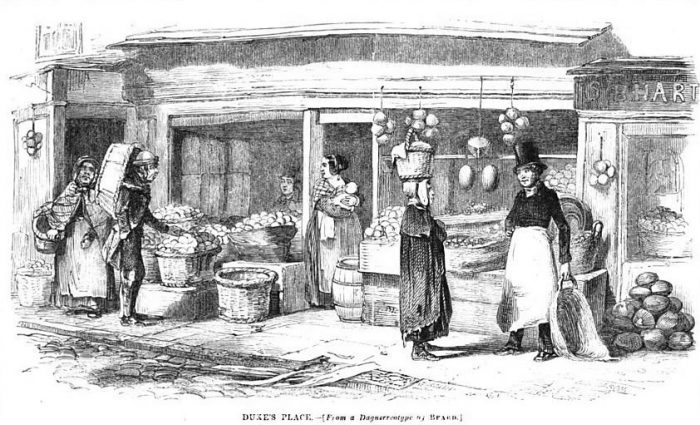

It seems that Thomas worked for several years as a chandler, rather than as a grocer. He set up shop at No. 12 Upper Cleveland Street in Fitzrovia, first appearing at the address in 1815.[1]Post Office Directory. It’s worth mentioning that while Thomas’ name appears in the directory, it was a Margaret Morrison of No. 12 Upper Cleveland Street who took out insurance at the … Continue reading It appears that the previous occupant of the shop premises was Robert (also known as Michael) Noble, a “fishmonger and potatoe dealer” who in June 1815 was “a prisoner for debt in his Majesty’s gaol of Newgate.”[2]Kentish Gazette, 27 June 1815

In January 1818 he appears to have been one of the witnesses to his sister Elizabeth’s marriage, with Sarah Nunn, possibly their sister. Elizabeth was only seventeen at the time. Then in October 1818, Thomas might’ve been throwing the rice and eating cake at the wedding breakfast again when his sister Sarah married John Barrell, as a Thomas Griffin witnessed Sarah’s marriage too.

I wonder if Elizabeth had moved to London to live with Thomas and help run his shop. Certainly the man she married went quickly from being a tobacconist at the baptism of their first child in 1819, to an oilman and chandler by the time their second child was baptised in 1822.

Thomas placed an advert in the Morning Post in 1822:

OIL, CANDLES, SOAP, &c. at T. GRIFFIN’S Manufactory, 12, Upper Cleveland-street, Fitzroy-square, near the New-road. – Fine Wax Candles 3s. 8d. per lb; Fine Sp*rm do. 3s. 2d.; Store do. 7s. 6d. per dozen; Fine Mould do. 9s, per do.; Best Mottled Soap 80s. per cwt.; Best Yellow do. 70s. per do.; Genuine Sp*rm Oil 5s. 9d. per gallon; Fine Scented Windsor Soap 1s. 6d. per lb. – T. Griffin, relying on the quality of the above-mentioned articles, begs leave respectfully to offer them at very reduced prices for ready money. – All letters must be post paid. – Country orders carefully attended to.

Morning Post, 23 March 1822 (Note: asterisks added to avoid the page being marked as saucy)

As he describes his business as a “manufactory”, we might imagine Elizabeth rolling up her sleeves and stirring vats of bubbling fat in order to make soaps and candles. Or perhaps she packaged up the Thomas clearly didn’t rely on passing trade, either, accepting orders from outside London. Somewhere, one supposes, there might still be T Griffin packaging. He evidently needed space to carry on his business. Nearly ten years before Thomas moved in, the sculptor Charles Regnart was at No. 12 Cleveland Street,[3]I’m not entirely sure if this is the same building as Thomas’ shop or it was at the other end of the street. selling both carved grave monuments to memorialise friends and relatives, and marble fireplaces. He is well-known enough to have his own Wikipedia page.[4]Morning Post, 12 May 1806 and 23 April 1807. I have to say, it’s not entirely clear if “Upper Cleveland Street” and plain “Cleveland Street, Fitzroy Square” are the same … Continue reading

In 1826, he married twenty-five-year-old Mary Cleaver at St Pancras, the parish that Upper Cleveland Street fell within at the time. Mary lived in the parish of St George Hanover Square – it may or may not be significant that Elizabeth and her husband David lived in that parish at the time they were married. Perhaps they knew each other.

Thomas was nearly forty years old when he married Mary, a widower. Quite who his first wife was is a mystery. She doesn’t appear to be anyone he married in Buckinghamshire or Hertfordshire, but there are several marriages in the London area for men called Thomas Griffin in the period between his becoming old enough to marry, and before he married Mary – yet narrowing it down is very difficult. Knowing how long Thomas lived on Upper Cleveland Street, though, is helpful. One day I might work it out! At the moment, the most likely marriage seems to be that of Thomas Griffin and Martha Belcher, both single, both of St George’s, Hanover Square, who married at that church on 12 March 1818. That same year, at the very same church, Thomas’ sister Elizabeth got married, as did his brother William, both of them resident in that parish at the time of their marriages.

The other thing that makes this tantalisingly likely is that one of the witnesses to the possible 1818 marriage for Thomas was Robert Slocombe. He was a wax and tallow chandler at No. 9 Charlotte Street (which, along with Duke Street, is now Hallam Street in Marylebone), less than half a mile away from Upper Cleveland Street (so it’s almost certain that Thomas Griffin would’ve known of him), and his wife was Elizabeth Belcher, born in Great Milton, Oxfordshire in about 1774.[5]Elizabeth was buried at St James’ on Hampstead Road in 1852, just by Euston Station. The church was demolished in the 1960s and the churchyard became St James’ Gardens, which has been … Continue reading They had married at St George Hanover Square, too, in 1808. Elizabeth had a sister called Martha, born in Great Milton in about 1787, so was only a year older than Thomas. As we’ve seen, siblings tended to move to London together, so it wouldn’t be surprising that Elizabeth’s sister had headed to the capital as well. What perhaps happened was that Martha lived with the Slocombes and worked in their shop, which meant that she knew Thomas Griffin, and was an ideal bride as she could help Thomas in his shop too. There is no burial for a Martha Griffin that fits, but a 34-year-old Mary Griffin was buried at St Marylebone on 25 April 1822. Her abode is given at Marylebone – what I wonder is if “Mary” should read “Martha” (these mixups do happen) and that she had fallen ill and was cared for by her sister on Charlotte Street until her death. Although Upper Cleveland Street was wholly in the parish of St Marylebone by 1851, even in 1834 it was half in St Marylebone and half in St Pancras as the border between the two parishes ran down its middle.[6]See the Topographical Survey Of The Borough Of St. Marylebone 1834 map. Upper Cleveland Street is in the bottom row, second square from the right. On Horwood’s plan of London, no. 12 seems to have been on the St Pancras side. It certainly feels plausible, but more evidence would be nice! That said, Thomas Griffin-as-witness’ signature is identical to Thomas-Griffin-as-groom’s.

The Cleavers and Gardners

Mary was born on 8 April 1801, one of six children born to Richard Cleaver and his wife Nanny Gardner between 1793 and 1807. She was baptised at the church of St James’ in Paddington a few weeks later. Richard worked as a cheesemonger on Edgware Road. Tragically, Mary lost both of her parents within a matter of months when she was only eight years old.

Robert Gardner, the children’s maternal grandfather, stepped in. When he wrote his will in 1817, he left his servant Jane Stevens £15 “in recognition of her care and attention towards my grandchildren” – presumably Nanny’s orphaned children, who Robert took in. He owned quite a lot of property and left Mary No. 126 Edgware Road, which appears to have been Robert’s home as he left Mary and her brother Richard all the household goods at the property as well.[7]PCC will of Robert Gardner of Edgware Road, gent, probate 18 April 1818, written 19 December 1817. He mentions his daughter Mary Butler of Hampstead, a widow; his daughter Sarah Bennett, wife of … Continue reading

George Coward, husband of Mary’s sister Ann, was one of the witnesses to Thomas and Mary’s marriage, along with Mary’s two youngest sisters, Eliza and Sophia. It’s possible that Mary was living with George and Ann at the time of her marriage as George was then a tailor living at No. 2 Hanover Street, in the parish of St George Hanover Square.[8]George and Ann had married in 1813. Sadly, George would pass away one year after Thomas and Mary were married. She was George’s sole legatee, and when she died in 1841, she was described as … Continue reading When George’s father wrote his will in 1812, he nominated John Peacock, a woollen draper from New Bond Street, to be one of his executors. Given the number of drapers in the Griffin family, it may be the case that John Peacock knew the Griffins. Although of course it’s not at all odd that a tailor would know a draper.

To Spitalfields

Thomas makes his last appearance as a wax and tallow chandler at 12 Upper Cleveland Street in Robson’s London Directory for 1834. After that, he disappears from the directories for a few years, apparently because the business ran into difficulties.

In April 1834, the contents of No. 12 were sold off:

Cleveland-street, Mary-le-bone. – Stock in Trade, Lease of Premises, Household Furniture, Utensils in Trade, &c.

By Mr OLIVER, on the Premises, No. 12, Cleveland-street, New-road, Mary-le-Bone, on Wednesday, April 30, at Ten precisely, by direction of the Mortgagee.

The Stock, &c., comprising tallow, oils, colours, brushes, pickles, candles, a tallow-copper, candle-machine, moulds, frames, boxes, rods, measures, cans, casks, feather beds, bedding, drawers, bookcase, an eight-day clock, chairs, tables, glass, and numerous other effects; the valuable lease of the premises will be sold on the same day, at one o’clock, together with shop-fixtures and fittings. May be viewed on the day preceeding; catalogues then had on the premises; and at the Auctioneer’s Offices, No. 7, Lawrence-lane, Cheapside.

Morning Advertiser, 25 April 1834

Thomas must’ve owed a lot of money, given that as well as selling off his stock and the very equipment he needed for making the candles that he sold, he was also having to sell off furniture, a clock, and even glasses. It must’ve been horrible to see everything that he’d worked for at No. 12 for nearly twenty years be auctioned off. He may have had to take this extreme option to avoid going bankrupt and thus spare himself going to debtor’s prison, as had the previous occupant of his shop back in 1815.

By August 1835, they were living at No. 18 John Street, only a few streets away from Upper Cleveland Street.[9]John Street, Tottenham Court Road is the address Thomas gave as his abode when he wrote his will on 1 August that year. John Street was, along with some other streets, renamed as Whitfield Street, … Continue reading They may have had to shut their own shop, but they might have been making ends meet by working as assistants in someone else’s shop. It doesn’t appear that they had moved in with relatives – as far as I know, none of them were living on John Street. Thomas’ father Daniel Griffin had died in January that year, and under the terms of Daniel’s will, his children wouldn’t inherit anything until his wife Elizabeth had died – and she lived until 1842. It seems that his father’s death led to Thomas writing his will, as he mentions the £100 to come from his father, which he leaves to his wife Mary.

There had been a shop at No. 47 Red Lion Street, close to Spitalfields Market, for many years, run by the Davies family. George Hugh Davies last appears as the grocer at that address in 1839; from 1840, Thomas Griffin steps in, working as a grocer and oilman.[10]The 1841 census described Thomas a grocer, and the 1851 census says he’s an oilman. At the inquest into Eliza Blount’s death in 1846, he was described as a grocer and oilman. George moved to No. 21 Saville Place, working with Frederick Bryant as a wine merchant at No. 30 Nicholas Lane, Lombard Street. When George was baptised in 1805, his father, William, was a chandler of Red Lion Street, and even ten years earlier when his brother William had been baptised, his father had been a chandler at the same address. From 1810 to 1836, there are seven records of the William “Davis”, grocer and chandler at No. 47, insuring himself with the Sun Fire company, along with other addresses where the family was carrying on business.

At their grocery, Thomas and Mary would’ve sold dried goods, like sugar, flower and dried fruit, along with candles and oil from the chandlery side of the business, and possibly soap. They may have sold butter and cheese too, although there were many dedicated cheesemonger’s shops around at the time. In fact, Thomas’ nephew Samuel Nunn would marry the daughter of a grocer and cheesemonger. Customers would shop in person at grocer’s but often would have their shopping delivered to them, so Thomas and Mary would have prepared orders and sent them out via delivery boys.

Tragedy at No. 47

At the end of 1845, Mary’s sister Eliza left her husband and lived with the Griffins at No. 47 Red Lion Street. Eliza had married a chemist called William Blount in 1828 at St Pancras, the parish she was living at the time – so it’s possible she had been living with her sister and her husband on Upper Cleveland Street. William ran a shop on Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, an eminently respectable address. It may have been that William sold Thomas’ soap at his shop, and that was how the couple had met.

But unfortunately, their marriage ran into difficulties. Quite what isn’t clear but the situation had become bad enough for Eliza to leave William, which was a big step to take at that period. Divorce was next to impossible for ordinary people because it required a private act of parliament until the 1850s, and even then it wasn’t a simple process. The Blounts had had “marital differences” which “had long existed”.[11]From the report of the inquest, The Era, 15 Feb 1846

By mid-February 1846, Eliza’s mood had dipped and she was very unhappy. One morning at about seven o’clock, Mary went up to Eliza’s room to call her, but didn’t find her there. Thomas went with Mary up to the attic of the house and there, sadly, they found Eliza. She had hanged herself. Thomas cut her down and set for a surgeon, who could do nothing for her.[12]From the report of the inquest, The Era, 15 Feb 1846. The inquest took place “yesterday”, 14th, and Eliza was found “the previous morning” so it seems she took her life on … Continue reading

Eliza was buried at St Mary’s, Paddington Green, where both her parents had been buried in 1809, and where her grandfather, Robert Gardner, had been buried nine years later. She had only been five years old when she had gone through the trauma of losing both her parents in the space of six months, and although she was evidently close to her sister Mary, it may have been that splitting up from her husband and the uncertain, unstable future that lay ahead played on the feelings of abandonment that she may have been carrying around with her since childhood.

Neither was that the only bereavement they had to bear. Back in 1841, Thomas’ brother-in-law David Nunn had died, leaving his forty-year-old widow, who was pregnant at the time, and their six surviving children. In 1847, the year after Eliza’s death, Elizabeth Nunn, David’s widow, died. She had been ill for eleven weeks, and a fortnight before her death, wrote her will, which Mary witnessed. Elizabeth was buried at Abney Park in Hackney, the then-fairly new cemetery for Dissenters. Two years later Sarah Nunn, Elizabeth’s eldest child (perhaps named after Sarah Fowler, Thomas and Elizabeth’s mother) died in the cholera epidemic that swept through Europe, killing thousands. Sarah had been left with the task of carrying on the family business, and now that fell to her younger siblings. As Mary had witnessed Elizabeth’s will, it seems likely that Thomas and Mary kept an eye out for their orphaned nieces and nephews in Shoreditch.

London evolves

Red Lion Street in Spitalfields no longer exists. In the 1840s and 1850s, the area underwent development. In 1815, David Hughson had written his book Walks Through London, and had mentioned Nicholas Culpeper, a famous resident of Spitalfields:

He died in 1654, in a house he occupied then in the fields, but now a public-house at the corner of Red Lion Court, in Red Lion Street, and which, though it has undergone several repairs, still exhibits the appearance of Old London.

David Hughson, Walks Through London, vol 2, 1815.

The area needed to be modernised. Red Lion Street became part of Commercial Road, and other parts of Spitalfields were demolished completely as the road carved its way through houses and shops that had stood for centuries but were sagging and on the point of falling down. Thomas and Mary were still at No. 47 in 1851, but only the next year, the fixtures and fittings of their shop were sold off.

SALES BY AUCTION

Spitalfields Improvements – To Oilmen and Grocers. – Fixtures and remaining Stock. By MR MASON, on Wednesday, May 5, on Premises, 47 Red Lion Street, to clear the premises.

THE SHOP FITTINGS and UTENSILS comprise wainscot-top counters, mahogany and other drawers, gas fittings, large lead and tin oil cisterns, beam and planks, scales, weights, measures, show glasses, casks, kegs, candle boxes, a large number of stone pickle jars, with a small quantity of tea, sugar, some candles, spices, oils, colours, &c. Also register and other stoves, oven and boiler range, copper, mahogany beaufet, and sundry furniture and effects. Catalogues at 7, Norton-folgate.

Morning Advertiser 22 April 1852 (advert repeated on 29 April, giving the auction date as Monday 3 May).

The advert allows us one last peak inside the Griffins’ shop.

They moved to No. 9 Coleman Street, New North Road in Islington, where Thomas died on 28 February 1860, aged about 72. He had written his will a few months after his father’s death in 1835, leaving everything he had to his wife, Mary:

…to Mary my beloved wife the sum of £40 from the Amicable Benefit Society held at the sign of the Pewter Platter, Charles Street, Hatton Garden and likewise the sum of £100 left me by my deceased father and further my household furniture, linen and plate and whatever property may belong to me at the time of my decease.

His will had been witnessed by John and Mary Ann Glazier, who also lived at No. 8 John Street.

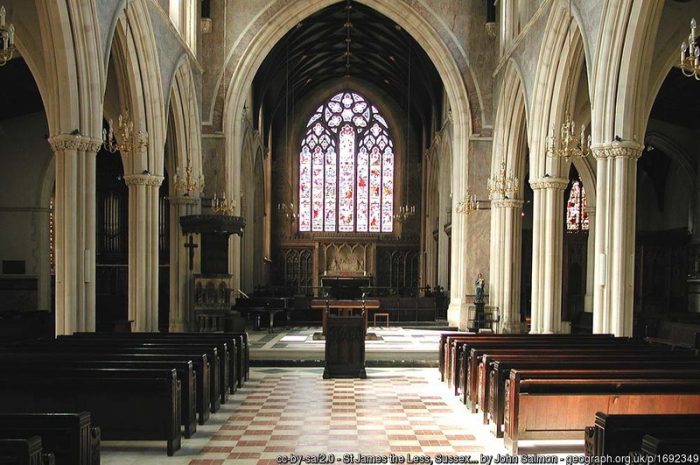

Thomas was buried at Abney Park cemetery on 6 March 1860, where his sister Elizabeth had been buried in 1847, although they didn’t share the same plot.

Mary was still living at Coleman Street when the census was taken in 1861, lodging in the home of David Humphreys. He was from Wales, a lath mender by day and a Methodist preacher of a Sunday. But she soon moved to 51 Buckland Street, where a man called Ebenezer Hyde also lived. By a huge coincidence, Ebenzer had been born in Wivenhoe, Essex, where his father had been the minister of the Independent chapel. That same chapel became Wivenhoe Congregational where, in the 1990s, Albert Henry Nunn, grandson of Thomas Griffin’s nephew Samuel Nunn, would be lay preacher.

Sadly, on 29 September 1862, 61-year-old Mary was admitted to Bethnal House, an hospital for people mental health issues. She died there less than three months later on 12 December. Given her sister Eliza’s struggle with mental health, Mary’s admission may suggest that there was a family tendency towards such problems. However, it may be that she had early on-set dementia, perhaps brought on by the loss of her husband. The register doesn’t specify what her condition was.

Mary’s will left everything to her sister, Sophia Fox, and Sophia’s children. She was buried at Abney Park with Thomas.

The lives of people like Thomas and Mary get overlooked as they didn’t have any children and are therefore a full stop in the family tree. But I think it’s worth taking the trouble to research them because not only does it allow us to see what people’s lives were like at this period, it also helps to see them within their own families and how those family relationships worked. Not that we can see them all that clearly without photographs or diaries or letters, but we can get fairly close. We can peak inside their shops, or even now stand on the streets where they lived. And one day, I plan to go to Abney Park and visit the place where they rest.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Post Office Directory. It’s worth mentioning that while Thomas’ name appears in the directory, it was a Margaret Morrison of No. 12 Upper Cleveland Street who took out insurance at the address with the Sun Fire Office in 1819. She doesn’t appear in the directories around this period. When she wrote her will in 1824, she was living at Upper Cleveland Street, but another insurance document from 1834 suggests she had moved by then to No. 47 High Street, Marylebone. Her will was proved in 1836 and doesn’t mention anyone to do with the Griffins, Nunns or Cleavers, so it may just be that she was a tenant in the house, though it can’t have been wonderful living above a shop full of flammables and someone making soap on an industrial scale. Then again, Londoners lived cheek-by-jowl at that period in a way that is hard for us to appreciate nowadays. She was buried at Bunhill Fields, the Dissenters’ main cemetery in London before the advent of places like Abney Park, on 18 May 1836. She was 72, from High St, New Road. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Kentish Gazette, 27 June 1815 |

| ↑3 | I’m not entirely sure if this is the same building as Thomas’ shop or it was at the other end of the street. |

| ↑4 | Morning Post, 12 May 1806 and 23 April 1807. I have to say, it’s not entirely clear if “Upper Cleveland Street” and plain “Cleveland Street, Fitzroy Square” are the same or not – Upper Cleveland Street is just around the corner from Fitzroy Square, so it does seem as if they are the same places. |

| ↑5 | Elizabeth was buried at St James’ on Hampstead Road in 1852, just by Euston Station. The church was demolished in the 1960s and the churchyard became St James’ Gardens, which has been excavated for the HS2 train project. This means that Elizabeth’s remains are among those to have been exhumed and moved away. |

| ↑6 | See the Topographical Survey Of The Borough Of St. Marylebone 1834 map. Upper Cleveland Street is in the bottom row, second square from the right. |

| ↑7 | PCC will of Robert Gardner of Edgware Road, gent, probate 18 April 1818, written 19 December 1817. He mentions his daughter Mary Butler of Hampstead, a widow; his daughter Sarah Bennett, wife of Joseph Bennett of Tottenham Court Road, St Pancras, a cabinet maker; his brother-in-law John Rolls of Kings Road, Chelsea, nurseryman (John Rolls married Alice Gardner in 1781 in Marylebone – there was a memorial inscription mentioning them in the churchyard of St Luke’s, Chelsea, which said that Alice died on 12 September 1822, aged 74, although the burial register says she was 79. The same memorial says John died on 23 September 1823, aged 70.); his grandson George Legg; Mary Ann Rolls and John Rolls, children of his late granddaughter Mary Ann Rolls; his granddaughter Ann, wife of George Coward; his grandson James Butler; his sister Elizabeth Allibone; then four of the Cleaver children: Richard, Mary, Eliza and Sophia. |

| ↑8 | George and Ann had married in 1813. Sadly, George would pass away one year after Thomas and Mary were married. She was George’s sole legatee, and when she died in 1841, she was described as “a lady of fortune” in the report of the inquest in the Morning Post, 25 September 1841. |

| ↑9 | John Street, Tottenham Court Road is the address Thomas gave as his abode when he wrote his will on 1 August that year. John Street was, along with some other streets, renamed as Whitfield Street, and is one block west of Tottenham Court Road, running parallel to it. Whitfield Street culminates in Windmill Street, which is where Thomas’ sister Elizabeth was living in 1819. |

| ↑10 | The 1841 census described Thomas a grocer, and the 1851 census says he’s an oilman. At the inquest into Eliza Blount’s death in 1846, he was described as a grocer and oilman. |

| ↑11 | From the report of the inquest, The Era, 15 Feb 1846 |

| ↑12 | From the report of the inquest, The Era, 15 Feb 1846. The inquest took place “yesterday”, 14th, and Eliza was found “the previous morning” so it seems she took her life on 13th February. Whether it is significant that this happened the day before Valentine’s Day isn’t known. |